You don’t have to be a statistician to notice that something is off in this year’s weather. That could change the whole national debate.

It’s been a tough few weeks for weather, as Atlantic’s Jacob Stern summarizes:

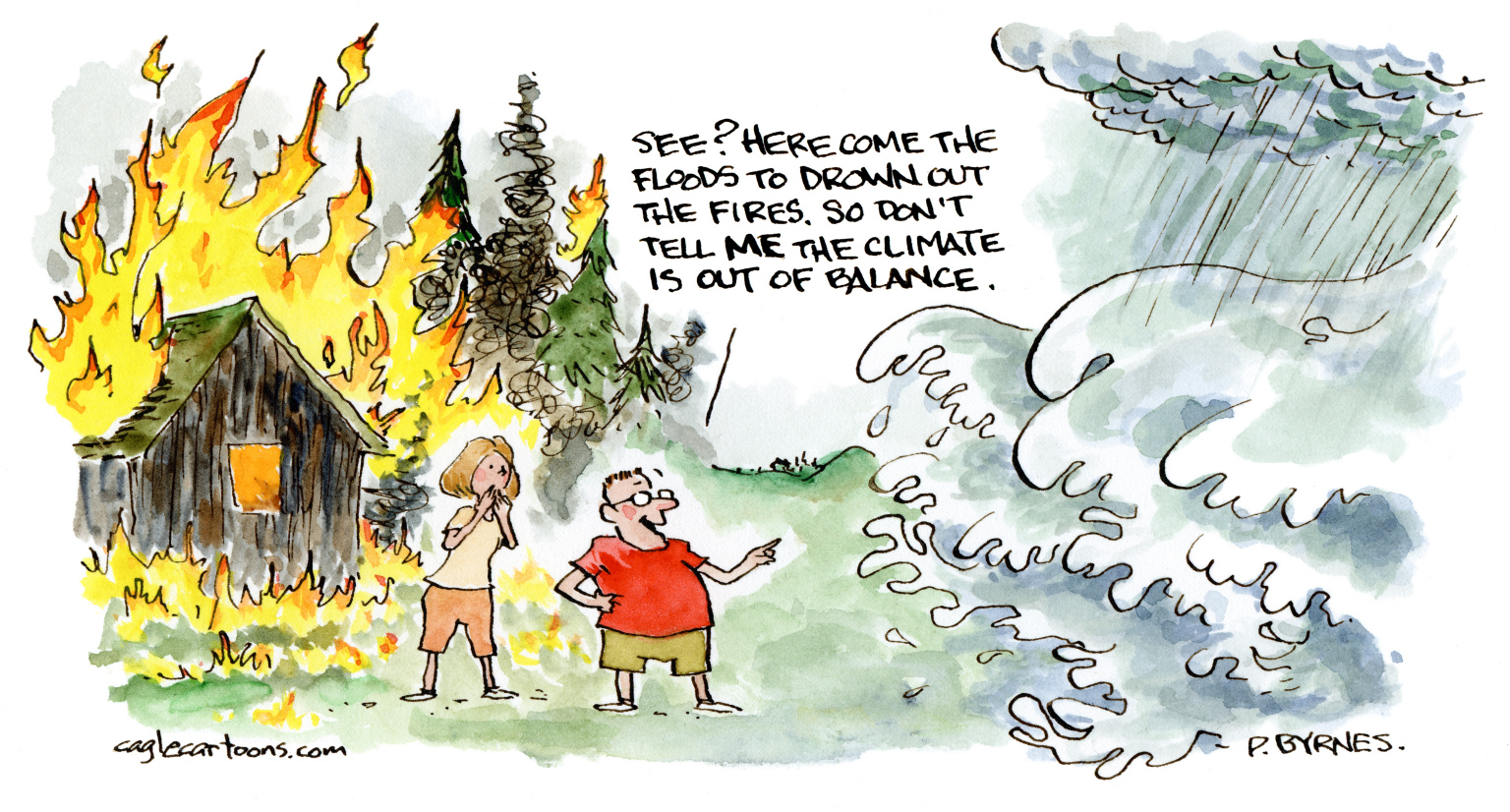

It’s getting hard to keep track of all the overlapping climate disasters. In Phoenix, Arizona, the temperature has broken 110 degrees for nearly two weeks running. The waters off the Florida coast are approaching hot-tub hot, and before long, marine heat waves may cover half the world’s oceans. Up north, Canada’s worst wildfire season on record burns on and continues to suffocate American cities with sporadic smoke, which may not clear for good until October. In the Northeast, floods have put towns underwater, erased entire roadways, and left train tracks eerily suspended 100 feet in the air. Also, the sea ice in Antarctica—which should be expanding rapidly right now, because, remember, it’s winter down there—may be losing mass.

Over the last ten or twenty years, we’ve gotten used to a certain pattern of debate about problematic weather.

- Something terrible happens: A hurricane levels New Orleans or floods New York, or wildfires get scarily close to a major city, or the Mississippi has a historic flood, or something else.

- Scientists explain how climate change contributed to the disaster.

- Climate deniers scoff, and point out that the world has always had heat waves and storms and floods and fires.

- The immediate threat abates: the heat wave breaks, waters recede, cities clean up, and life more-or-less goes back to normal for a few weeks or months.

- Media attention moves on.

For most people, the significance of these blips of bad news is hard to sort out, because both sides have ways of fitting such events into their favored narrative: Either “The clock is continuing to tick down towards a climate apocalypse”, or “Environmentalists keep trying to scare us, but life goes on.”

Trying to break through that endless back-and-forth leads scientifically-minded people to apply statistics: Yes, there have always been natural disasters, but not this often. For example, what used to be a hundred-year flood now comes once a decade, or maybe even sooner.

But statistics can’t solve the public-perception problem, because the people who need to be convinced are precisely the not-scientifically-minded folks, the ones who distrust “experts” and especially distrust mathematical models and other ways of measuring things that they couldn’t have come up with on their own.

In general, non-scientists are only impressed by a statistic if they were already paying attention to it before the latest event. You can see this phenomenon in non-political arenas like sports. In 1998, for example, baseball fans everywhere were fixated on Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa’s chase after the Ruth/Maris single-season home run record. That’s because every baseball fan already knew that Babe Ruth had hit 60 home runs in 1927 and Roger Maris hit 61 playing a longer season in 1961. McGwire and Sosa were racing towards a finish line that had been marked out for decades.

By contrast, look at the season Aaron Judge had last year: By some accounts, it may be the best season a hitter has ever had. But to make that claim, you have to cite advanced statistical measures that most fans have never heard of and could not calculate for themselves: WAR, OPS+, RV+ and so on. So while every fan recognizes that Judge’s 2022 was a really good year — his 62 home runs surpassed Maris’ 61, which was still the record for the American League — it lacked the drama of 1998, and the best-ever arguments feel like something cooked up after the fact.

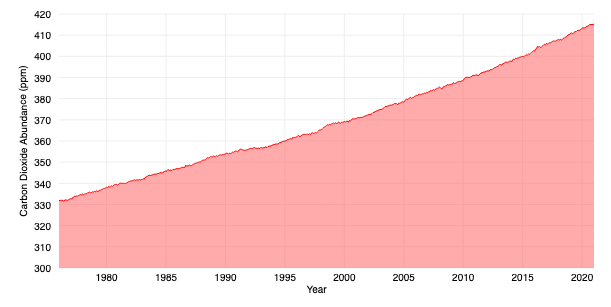

Same thing for global average temperature, which looks headed for a new record this year, breaking the one set in 2016 and nearly equaled in 2020. Ordinary people can put thermometers on their porches and measure temperature here and now, but they can’t measure and can’t check global average temperature, which is compiled through a complex statistical process. Sure, somebody like NOAA or NASA may claim it’s setting a record, but other people claim those numbers are cooked up, and that NOAA is “just another deep state bureaucracy with a political agenda“, so who’s to say?

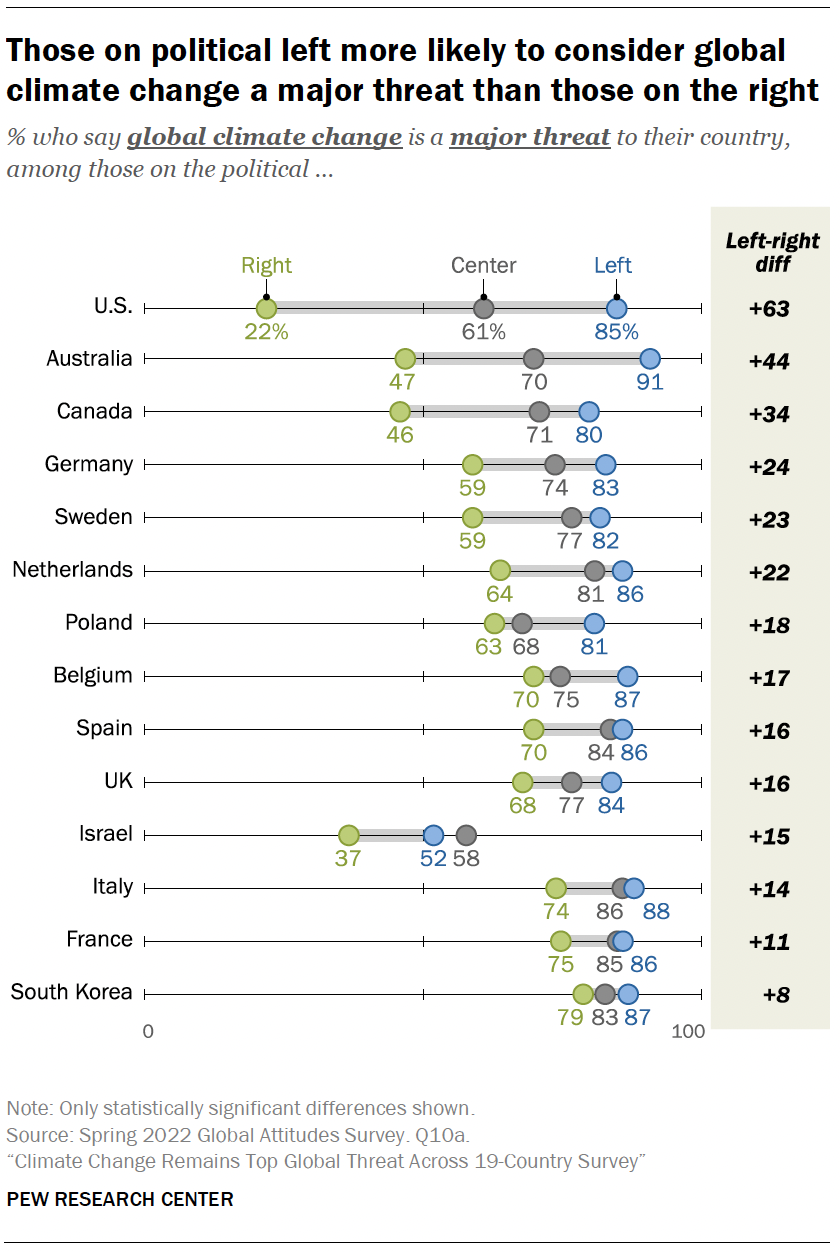

The result is that American public opinion on climate change displays the same left/right split that you’ll see on more values-based issues like abortion or affirmative action. As the chart below (from Pew Research) shows, the US is unusual in this regard. In South Korea, climate change is barely a partisan issue at all, and a right-leaning voter in the UK is three times more likely to consider climate change a “major threat” than his American cousin. (If you can explain what’s going on in Israel, where left-leaning voters worry about the climate less than anywhere else in the world, leave a comment.)

This summer’s combination of disasters is an opportunity to break out of this left/right pattern. When one disaster starts before the previous one ends, and record-setting heat in Florida and Texas competes for headlines with unprecedented floods in Vermont and Pennsylvania, we’re in new territory. You don’t need any statistics or expert analysis to recognize that the weather never used to do stuff like this. “Bad things didn’t used to happen this often” is a statistical claim. But “Bad things didn’t used to happen all at once” is something ordinary people can verify through our own experience.

Whatever their political loyalties, just about all Americans must know in their hearts that something is seriously wrong, and that the kinds of predictions that got labeled as “alarmist” or “fear-mongering” a few years ago are starting to come true. We’re no longer talking about projections of problems our grandchildren will face. We’re looking at what’s happening here and now.

Environmental activists and their allied politicians (who are almost all Democrats) need to run with that perception. In the past, the burden has been on them to use expert analysis to explain away the average American’s impression that life was continuing more-or-less normally. But going forward, the tables will have turned: It will be climate deniers who will need to make complicated arguments to explain away the public’s perceived reality.

Going forward, the role of long-term climate models will also change. The point won’t be to make apathetic people worry about the future. Instead, the models will explain to people who are already worried that things are only going to get worse until we make major changes.

Americans also know in their hearts that in the long run it’s more cost effective to prevent disasters than to clean up after them. Yes, it will require substantial investment to convert our economy to renewable energy, to modernize the electrical grid, and shift our consumption patterns away from fossil-fuel intensive products. But those investments will not only create jobs in the present, they’ll save money overall.

And the long-term models will also play another role: As sweeping changes get proposed, we’ll need expert analysis telling the public “This can work.” The models that have been carrying messages of despair could also carry messages of hope.