This was a week where you couldn’t tell the players without a program. Important things were happening in multiple Trump trials at once — a phenomenon I think we’ll see more of in the months ahead. But before going into the details, I want to talk about the general phenomenon: Why does Donald Trump keep losing in court?

Why Trump keeps losing. Friday, New York Judge Arthur Engoron issued his decision in the New York civil fraud case against Donald Trump, his adult sons, several Trump Organization companies, and two major Trump Organization executives: a $355 million “disgorgement” penalty, plus interest.

This is a huge amount of money, and it is just the latest of a series of Trump losses in court: the two E. J. Carroll lawsuits for defamation and sexual assault, which resulted in $88 million in damages; the criminal tax-fraud case against the Trump Organization ($1.6 million from the company and jail time for ex-CFO Allen Weisselberg); the Trump University civil fraud suit (settled out of court for $25 million), the Trump Foundation lawsuit ($2 million and dissolution of the foundation), and 61 of the 62 suits Trump filed in his attempt to overturn his loss in the 2020 election. (The one he won affected a tiny number of votes and had no effect on the election’s outcome.)

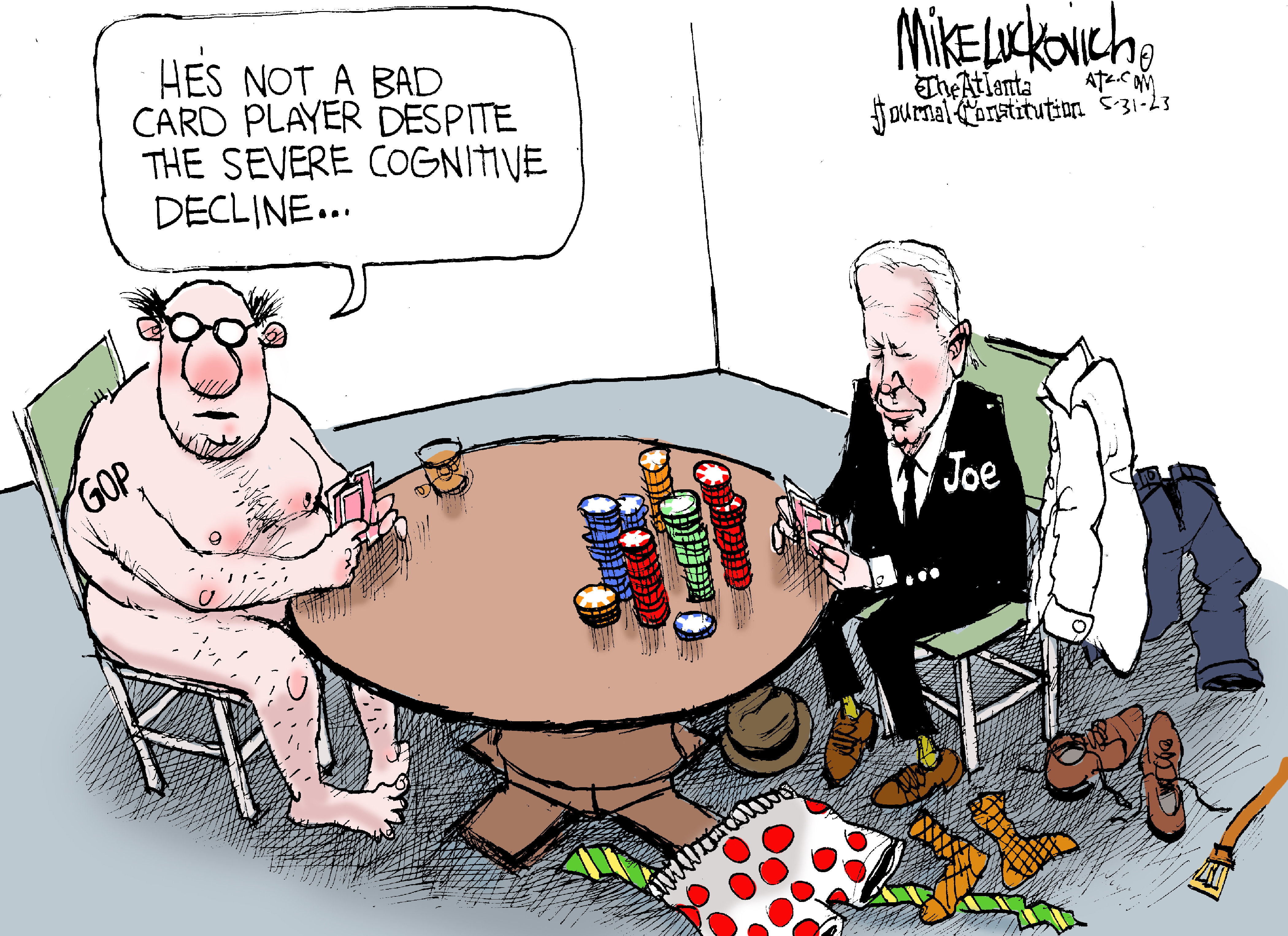

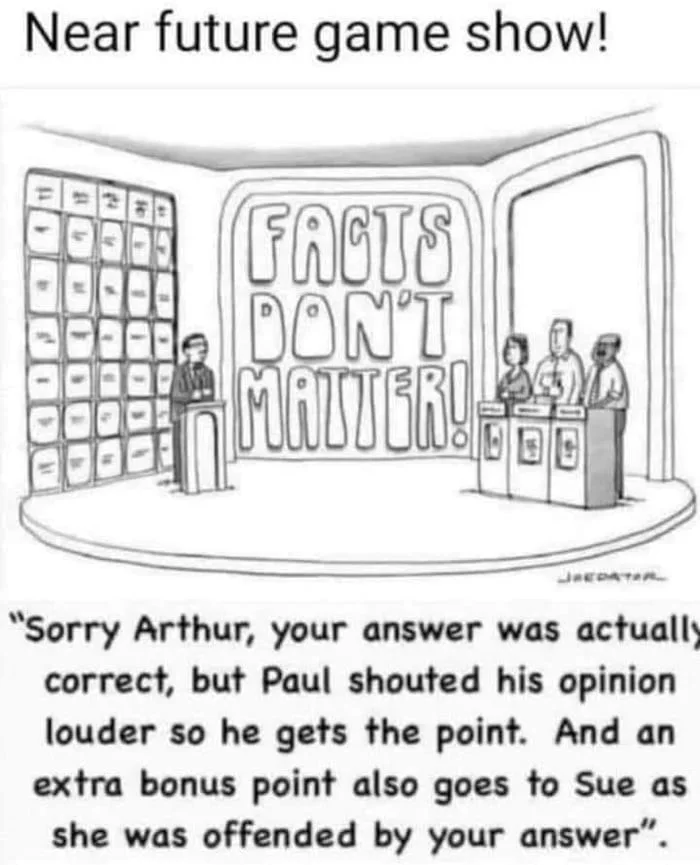

Trump, of course, paints this as years of harassment by a corrupt legal system, but I learn a much simpler lesson: Bullshitters don’t do well in court. A talented bullshitter can succeed in politics and/or business, but judges don’t have to put up with bullshit, and most of them won’t.

When he’s been caught doing something wrong, Trump’s usual damage-control technique is to spin out several mutually inconsistent stories until he sees which one is catching on. (January 6 is a great example: At first, the rioters were antifa rather than his supporters. Then they were his supporters, but they were conducting a mostly peaceful protest. Or maybe it was a riot, but he didn’t incite it. And now we’ve reached the point where it was a riot and they were his supporters, but they are patriots being railroaded by the same corrupt legal system that is railroading him.) His supporters latch on to whichever explanation rings true to them, ignoring the fact the Trump himself may have moved on to a different story.

He tried something similar in the NY civil-fraud trial: He claimed his financial statements weren’t false. Or maybe they were false, but they had a disclaimer. Besides, accuracy was the accountants’ responsibility, not Trump’s. In real estate, everybody’s financial statements are false. And the bankers are sophisticated people who should have known not to believe Trump’s claims. Pick whichever answer appeals you.

Trump’s string of losses demonstrates that his tactic doesn’t work in court, where the legal process is designed to reach a single narrative of events. Shifting back and forth from one excuse to another will just annoy a judge, who will communicate that annoyance to a jury, if there is one.

Another thing that doesn’t work in court is restarting arguments you’ve already lost. Trump’s lawyers keep repeating defenses that Engoron had already ruled against. (Like: The loans were repaid, so there was no fraud. More about this below.) That kind of doggedness can pay off in politics, because the public easily forgets how some point was debunked. But in court it just pisses a judge off.

The $355 million civil fraud decision. Here’s Judge Engoron’s 92-page decision. Or you can read the NYT-annotated version.

The judge also added interest to the penalty, bringing the total to around $450 million. He denied the state’s request to ban Trump permanently from doing business in New York, and instead banned him for only three years, with sons Eric and Don Jr. banned for two. Engoron also decided not to revoke the Trump Organization’s certification to do business in New York (part of his earlier summary judgment that an appeals court had put a stay on), which would have effectively dissolved the company, since it is incorporated in New York.

The decision is dull reading, because Engoron goes through the witnesses one-by-one, summarizing what each one said and why it was believable, unbelievable, or irrelevant. Then he goes through Trump’s fraudulently valued properties one-by-one and lays out the evidence of fraud. This is important material to record for Trump’s inevitable appeal (since the appellate court won’t hold its own trial), but it can be tiresome to plow through.

Here are a few simple things I gleaned from the decision:

First, the shape of the fraud: When The Trump Organization was looking for loans during the 2010s, Deutsche Bank’s Private Wealth Management Division was the only bank that wanted to do business with them. In a series of deals, it offered two loan possibilities: a loan secured only by the real estate collateral, or a loan secured by the collateral plus Trump’s personal guarantee. The second loan had a significantly lower interest rate, and it was based on assertions about Trump’s net worth and available cash. Trump was then obligated to give Deutsche Bank annual statements of financial condition (SFCs) verifying that his net worth and available cash were still above certain thresholds.

Those SFCs are the fraudulent business records, and they were off by a lot. One type of fraud was to value Trump’s properties “as if” rather than “as is”. So for example, Mar-a-Lago is worth a lot more if it can be sold as a private residence, but its deed restricts it to being a social club. (Trump got a lower real-estate tax rate by agreeing to that restriction.) The SFCs list the value as if that restriction could be made to go away. Similar things happen all over the Trump empire: One property is valued as if Trump had permission to build 2500 residences, when in fact he only had permission to build 500. And so on.

Second, where did the $355 million figure come from? Engoron didn’t just pull it out of a hat, and punitive damages play no role. It is a disgorgement of ill-gotten gains. Basically, it’s the interest Trump saved by making the fraudulent guarantees, plus the capital gain from the sale of the Old Post Office hotel near the White House (which Trump would not have been able to buy without the fraudulently obtained loan). Eric and Don Jr. each give up $4 million, because that was their share of the Old Post Office gain.

Third, the fact that the penalty is a disgorgement is why Trump’s there-is-no-victim rhetoric is off-base. The point here isn’t to compensate a victim, it’s to protect “the integrity of the marketplace” by punishing fraud. Engoron quotes a precedent:

Disgorgement is distinct from the remedy of restitution because it focuses on the gain to the wrongdoer as opposed to the loss to the victim . Thus, disgorgement aims to deter wrongdoing by preventing the wrongdoer from retaining ill-gotten gains from fraudulent conduct.

By asking for the personal guarantee and demanding evidence of the wealth to back it up, Deutsche Bank was trying to protect itself against a possible downturn in real estate in general and in Trump’s fortunes in particular. As it happens, those risks didn’t manifest and the loans were repaid. But Engoron observes: “The next group of lenders to receive bogus statements might not be so lucky.”

This kind of disgorgement happens all the time in insider-trading cases: The SEC makes the traders give up their gains, even if it’s impossible to figure out exactly who they cheated. And the purpose is the same: to protect the integrity of the market by preventing cheaters from prospering.

Finally, I want to turn around one standard conservative criticism, which you’ll hear whenever Biden tries to forgive college loan debt: “But what about the people who follow the rules, the ones who took their debts seriously and paid them off? What do you say to them?”

In this case, what about the people who have been denied loans (or had to pay a higher sub-prime interest rate) because they filled out their applications honestly? Or people who can’t afford to pay an accountant to lie for them, the way Trump can? What do Trump’s defenders say to them?

The hush-money criminal case will go to trial March 25. This is the red-headed stepchild of the Trump indictments, but it looks like it will be the first one to go to trial. Slate’s Robert Katzberg expresses what I think everybody is thinking:

While the conduct charged is, no doubt, criminal, it feels a bit like prosecuting John Gotti for shoplifting. The Bragg prosecution is also clearly the weakest of the four outstanding indictments from an evidentiary perspective, especially when compared to the D.C. slam-dunk. … In an ideal world the D.C. prosecution would be first, allowing the world to see just how close we came to having the 2020 election overturned and the frightening degree to which the former president is a threat to our democracy. However necessary and appropriate that would have been, it is not where we are now. The Bragg case, while hardly the most desirable opening act, at least gets the show on the road.

This case stems from Trump paying off porn star Stormy Daniels to keep their affair secret during the 2016 presidential campaign. But the sex itself isn’t a crime and the fact of the payoff isn’t what’s being prosecuted: It’s the lengths Trump went to in order to hide the payoff from voters in 2016. He had Michael Cohen pay Daniels. Then the Trump Organization created a false paper trail to reimburse Cohen, and recorded the reimbursement as a business expense when it was actually a campaign expense. So the charge is falsification of business records.

The Georgia case. The RICO case against Trump and his election-stealing co-conspirators is currently on hold while the judge decides whether DA Fani Willis should be disqualified.

The issue is her romantic entanglement with another prosecutor on the case, who she hired, and the claim that he kicked back some of the money she is paying him by spending it on her during their affair, which they both claim is now over. (They both claim she paid her own way by reimbursing him in cash, leaving no records — which is a sensible thing to do if you hope to keep the affair secret.)

The stakes in this are huge, because if Willis is disqualified, quite possibly nobody else picks the case up and Trump walks. Certainly the case won’t be tried before the election.

On the other hand, that outcome seems unlikely to a number of observers, for this reason: Willis’ affair is certainly salacious and embarrassing, and it may even be unethical enough to result in some kind of discipline against Willis outside this case. But disqualifying her from this case requires showing prejudice against these defendants. And nothing they’ve put forward so far proves that.

As a matter of both common sense and Georgia law, a prosecutor is disqualified from a case due to a “conflict of interest” only when the prosecutor’s conflicting loyalties could prejudice the defendant leading, for example, to an improper conviction. None of the factual allegations made in the Roman motion have a basis in law for the idea that such prejudice could exist here – as it might where a law enforcement agent is involved with a witness, or a defense lawyer with a judge. We might question Willis’s judgment in hiring Wade and the pair’s other alleged conduct, but under Georgia law that relationship and their alleged behavior do not impact her or his ability to continue on the case.

My social media is full of a point that may not be legally relevant, but packs a political punch:

So Clarence Thomas can accept hundreds of thousands in gifts but Fani Willis can’t go dutch on dinner?

Jack Smith and presidential immunity. The question of whether former presidents are immune from prosecution for anything they did in office is now with the Supreme Court. Both Judge Chutkan and the DC Court of Appeals have rejected Trump’s immunity claim, which appears to be far-fetched and intended as a delaying tactic.

So far the delaying strategy is working: The trial in this case was originally supposed to start March 4.

Other than Trump and his lawyers, I haven’t heard anyone predict that the Supreme Court will reverse the lower courts’ rulings and stop Jack Smith’s January 6 case in its tracks. However, it remains to be seen to what extent Trump allies on the Court will cooperate with his strategy to delay the case past Election Day.

(As I’ve commented before, Trump’s delay strategy is essentially an admission of guilt. An innocent man who believed he was being prosecuted purely for political reasons would want the case to be tried as soon as possible, so that he could get the vindication of a jury’s not-guilty verdict. But Trump knows that a jury that sees the evidence will convict him, so his best hope is to get reelected and then instruct his attorney general to drop the case.)

The key documents have already been filed with the Court: Trump’s application for a stay that will continue delaying the trial, Jack Smith’s response, and Trump’s reply to Smith. The arguments Trump’s lawyers are making are the same ones the lower courts rejected, and amount to “No, they’re wrong.” (BTW: I love that this case is Trump v the United States.)

The Court has a number of options, which Joyce Vance outlines, ranging from refusing to hear the appeal and letting the case continue as soon as possible, to scheduling lengthy briefings and not ruling on the case soon enough for the trial to be heard before the election.

Disqualification. We’re still waiting for the Supreme Court to rule on whether the 14th Amendment’s disqualification clause applies to Trump (because of his role in the January 6 insurrection), and whether states (like Colorado) can enforce that disqualification from public office by refusing to list him on presidential ballots.

The judges sounded skeptical during the oral arguments, so it would be a shock if they ruled Trump ineligible. But it will be a challenge to square a Trump-is-eligible ruling with the conservative justices’ originalist philosophies. The Court works on its own clock, so a ruling could come tomorrow, at the end of the term in June, or any time in between.