Should we “fear for our democracy”, or is that reaction

“wholly disproportionate to what the Court actually does”?

In their dissents in the Trump immunity case, Justice Sonya Sotomayor explicitly expresses “fear for our democracy” and Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson warns that “the seeds of absolute power for Presidents have been planted”. But in his majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts dismisses such concerns:

As for the dissents, they strike a tone of chilling doom that is wholly disproportionate to what the Court actually does today

So who is right? In granting Donald Trump nearly all the immunity he asked for, did the Court “reshape the institution of the Presidency” and “make a mockery of the principle, foundational to our Constitution and system of Government, that no man is above the law”, as Sotomayor claims? Or did it simply make explicit principles that since the Founding have been implicit in the separation of powers and in Article II’s concise “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America”?

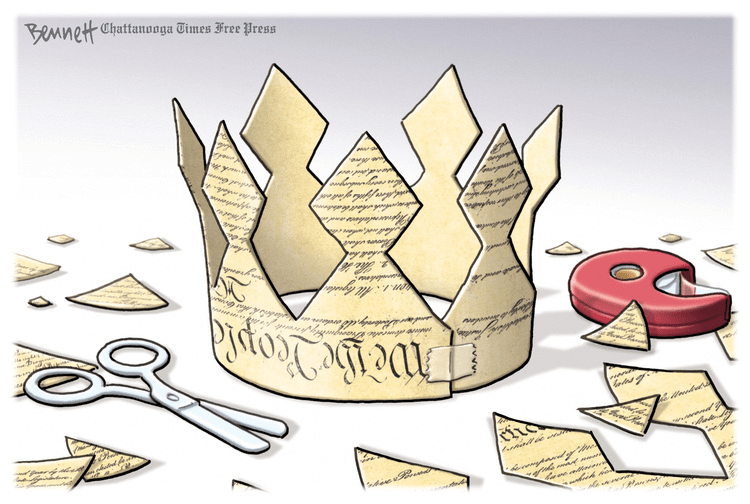

I won’t leave you in suspense: Sotomayor and Jackson are right. Roberts and the conservative majority have embedded a time bomb in the Constitution. That bomb could sit peacefully for decades until it is disarmed by some future Court, or it could go off as soon as next January.

What is this case about? Trump v United States arises from the indictment being prosecuted against Donald Trump (now a private citizen) in regard to his attempt to hang onto power by fraud and force after being defeated in the 2020 presidential election. While it is often referred to as “the January 6 case”, the indictment presents the January 6 riot not as a one-day event, but in the context of Trump’s months-long attempt to delegitimize the election that he lost and monkeywrench the usual constitutional and procedural processes that lead to the peaceful transfer of power.

The first steps of that effort were lawful, as Trump and his allies filed many dozens of lawsuits to challenge the election results in various states. These suits were routinely swatted down by courts that demanded evidence commensurate with Trump’s outlandish claims of fraud and procedural malfeasance, as well as his calls for unprecedented responses to those claims. He had no such evidence to present, and no further evidence has emerged in the subsequent years.

From there, Trump pressured state and local election officials to refuse to certify the election results. Up to a point, this too might have been lawful, as any candidate for office might suggest that officials look into election procedures he found suspicious. But much of it seemed to cross a line, as when Trump pressured Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to “find” the votes he needed to win Georgia, and suggested Raffensperger could be prosecuted if he didn’t.

Trump then tried to leverage the authority of the Justice Department, by having DoJ write letters to legislatures in states that Trump lost, falsely claiming that an investigation had found fraud in their elections and suggesting that they hold special sessions to replace the Biden electors the voters had chosen. Justice Department officials refused, and threatened to quit en masse if Trump appointed a puppet attorney general to send such letters.

The next step was to recruit fake electors who would present fraudulent papers to Congress claiming that their votes for Trump were the official Electoral College votes for their state, allowing either Vice President Pence or Congress as a whole to declare either that Trump had won or that the result of the election was unclear, initiating constitutional chaos that he hoped to turn in his favor.

As part of his pressure campaign on Vice President Pence and Congress, Trump assembled a mob on January 6 and sent them to the Capitol. They proceeded to battle police (injuring more than 100), invade the Capitol, and send members of Congress (and the vice president) running for their lives. While this was happening, Trump watched the riot on television, refusing for hours either to ask the rioters to go home or to call out the national guard to restore order.

The legal process. After many delays, this case was nearly ready to go to trial when Trump’s lawyers claimed the indictment was unlawful because the former president had “absolute immunity” from prosecution for any actions taken during his term in office. Special Prosecutor Jack Smith, recognizing the likelihood that the question would go to the Supreme Court eventually and hoping to get the trial done before the fall election, asked the Court to take the case on an expedited basis in December. They refused.

The case then went through the ordinary process, with every judge involved rejecting Trump’s immunity claim. For example, a unanimous three-judge panel from the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals declared on February 6:

For the purpose of this criminal case, former President Trump has become citizen Trump, with all of the defenses of any other criminal defendant. But any executive immunity that may have protected him while he served as President no longer protects him against this prosecution.

Most court-watchers and legal scholars found the appellate court ruling compelling, and many expected the Supreme Court to let it stand without a further hearing. When the Court did take up the case two weeks later, even court-watchers skeptical of the conservative majority’s motives saw the move simply as an attempt to aid Trump by delaying his trial past the election. [1] The Court’s scheduling — hearing arguments in April on the last day for hearing arguments and announcing the results on the last day of the term in July — seemed to confirm that suspicion. Right up to the decision’s announcement on July 1, few anticipated that the Court might find in Trump’s favor.

But they did.

What did the Court decide? As far back as the oral arguments in April, it was clear that the Court was going far afield from the case the appellate court had considered. Both the appellate court and the district court had focused the case in front of them: Trump’s claim of immunity for the acts alleged in the grand jury’s indictment. But the conservative justices showed little interest in the details of what happened on January 6 or the events that led up to that riot. Instead, they discussed abstract theories about executive power and elaborate hypothetical situations bearing no resemblance to the case at hand. [2]

So instead of a decision on whether the case against Trump should move forward, the conservative justices (excluding Barrett on at least one key point we’ll get to) laid out the following theoretical framework.

- There is absolute immunity “with respect to the President’s exercise of his core constitutional powers”.

- Presidents also have “at least presumptive immunity” for all other official acts “unless the Government can show that applying a criminal prohibition to that act would pose no ‘dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch’.” [The internal quote is from Nixon v Fitzgerald, which will come up a lot]

- There is no immunity for “unofficial acts”, but prosecuting even these acts might be difficult, given that “courts may not inquire into the President’s motives”, and official acts cannot even be presented “as evidence in a criminal prosecution of a President”. [3]

The Trump case will be sent back to the District Court so that Judge Chutkan can apply the Court’s principles to the indictment.

How does Roberts justify this ruling? Not very well, and not at all consistently with the conservative majority’s “originalist” or “textualist” philosophy. As Sotomayor points out:

It seems history matters to this Court only when it is convenient.

Criminal immunity for the president is mentioned nowhere in the Constitution, in spite of the fact that (as Sotomayor points out) at the time several state constitutions gave immunity to their governors. So it’s unlikely this significant provision just slipped the Founders’ minds. It also appears nowhere in American history, and some historical events make no sense if criminal immunity is assumed. (Why, for example, did President Ford offer Richard Nixon a pardon, and why did he accept it?) In justifying his vote not to impeach Trump for January 6, Mitch McConnell said:

President Trump is still liable for everything he did while he was in office as an ordinary citizen, unless the statute of limitations is run, still liable for everything he did while he’s in office. He didn’t get away with anything yet — yet. We have a criminal justice system in this country. We have civil litigation. And former presidents are not immune from being accountable by either one.

At the time, this point was not considered controversial. Trump’s own lawyer had told the Senate

If my colleagues on this side of the chamber actually think that President Trump committed a criminal offense, and let’s understand, a high crime is a felony, and a misdemeanor is a misdemeanor. The words haven’t changed that much over time. After he’s out of office, you go and arrest him.

Literally no one in America [4] believed in presidential criminal immunity until Trump raised the issue in his recent trials.

Roberts’ main argument is that if the the president is subject to future prosecution he might “be chilled from taking the ‘bold and unhesitating action’ required of an independent Executive”. He projects this opinion into the minds of the Founders by quoting Alexander Hamilton and George Washington lauding “vigor” and “energy in the executive” as an advantage the new Constitution offered over the old Articles of Confederation. However, he gives us no quotation in which this “energy” is connected to immunity from prosecution (because there is none).

Sotomayor writes:

In sum, the majority today endorses an expansive vision of Presidential immunity that was never recognized by the Founders, any sitting President, the Executive Branch, or even President Trump’s lawyers, until now. Settled understandings of the Constitution are of little use to the majority in this case, and so it ignores them.

Lacking any support in the text of the Constitution or American history, Roberts rests most of his argument on the precedent Nixon v Fitzgerald, the source of that “bold and unhesitating action” quote, in which the court ruled that presidents were immune from civil litigation based on their official acts. Roberts repeatedly quotes Fitzgerald, largely ignoring one substantial difference between civil suits and criminal indictments: Anyone can file a lawsuit, which (until a trial is held) is a “mere allegation” (as Fitzgerald puts it and Roberts quotes). But a criminal indictment comes from an impartial grand jury, and deserves considerably more respect. It easy to imagine an ex-president being peppered with thousands of frivolous lawsuits. But if multiple grand juries are finding probable cause that a president committed crimes, that seems like a more serious situation.

Nor may courts deem an action unofficial merely because it allegedly violates a generally applicable law. … Otherwise, Presidents would be subject to trial on “every allegation that an action was unlawful,” depriving immunity of its intended effect.

Again, the quote is from Fitzgerald, as if a grand jury indictment were simply an allegation.

The dissents’ positions in the end boil down to ignoring the Constitution’s separation of powers and the Court’s precedent and instead fear mongering on the basis of extreme hypotheticals about a future where the President “feels empowered to violate federal criminal law.” The dissents overlook the more likely prospect of an Executive Branch that cannibalizes itself, with each successive President free to prosecute his predecessors, yet unable to boldly and fearlessly carry out his duties for fear that he may be next.

But this problem never occurred before Trump, who both committed multiple crimes in office and now threatens to gin up sham prosecutions against President Biden, should he regain power. This is not a structural problem in American government; it’s the consequence of one man’s vices.

Sotomayor responds:

The majority seems to think that allowing former Presidents to escape accountability for breaking the law while disabling the current Executive from prosecuting such violations somehow respects the independence of the Executive. It does not. … [T]he majority believes that a President’s anxiety over prosecution overrides the public’s interest in accountability and negates the interests of the other branches in carrying out their constitutionally assigned functions. It is, in fact, the majority’s position that “boil[s] down to ignoring the Constitution’s separation of powers.”

Roberts three-part division. Roberts sketches out three zones: absolute immunity, presumptive immunity that can be overcome in certain situations, and no immunity. How much comfort should this system give us?

Not much, in my opinion. The need for a very small zone of protection appears in our history: Congress shouldn’t be able to make laws that restrict a president’s constitutional powers, and then try to prosecute him for violating those limits. This happened after the Civil War, when Congress made a law preventing President Andrew Johnson from firing cabinet officials, and then impeached him for breaking it. We can easily imagine Congress restricting the pardon power, say, by banning a president from pardoning members of his family or his administration. If he did so anyway, a subsequent administration might prosecute him. A court would be justified in tossing out such prosecutions before trial.

Sotomayor finds this kind of immunity irrelevant to the current case.

In this case, however, the question whether a former President enjoys a narrow immunity for the “exercise of his core constitutional powers,” has never been at issue, and for good reason: Trump was not criminally indicted for taking actions that the Constitution places in the unassailable core of Executive power. He was not charged, for example, with illegally wielding the Presidency’s pardon power or veto power or appointment power or even removal power. Instead, Trump was charged with a conspiracy to commit fraud to subvert the Presidential election

But Roberts’ zone of absolute immunity is much larger, and includes immunity for everything a president might do with his core powers. In the current case, this blows away the part of the indictment where Trump attempted to induce the Justice Department to send that false letter to the Georgia legislature.

The indictment’s allegations that the requested investigations were “sham[s]” or proposed for an improper purpose do not divest the President of exclusive authority over the investigative and prosecutorial functions of the Justice Department and its officials. And the President cannot be prosecuted for conduct within his exclusive constitutional authority. Trump is therefore absolutely immune from prosecution for the alleged conduct involving his discussions with Justice Department officials.

Testimony about such discussions cannot even be used to inform a jury’s evaluation of a president’s unofficial actions.

If official conduct for which the President is immune may be scrutinized to help secure his conviction, even on charges that purport to be based only on his unofficial conduct, the “intended effect” of immunity would be defeated.

Again, the quote is from Fitzgerald, who was talking about civil lawsuits, not criminal charges. Again, this removal of any “scrutiny” is where Barrett diverged from Roberts. [3]

In the zone of presumptive immunity, the presumption is almost impossible to overcome. The prosecution must “pose no ‘dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch’.” Sotomayor notes that this is a much higher bar than any precedent can justify.

No dangers, none at all. It is hard to imagine a criminal prosecution for a President’s official acts that would pose no dangers of intrusion on Presidential authority in the majority’s eyes. Nor should that be the standard. Surely some intrusions on the Executive may be “justified by an overriding need to promote objectives within the constitutional authority of Congress.” [Nixon v. Administrator of General Services]. Other intrusions may be justified by the “primary constitutional duty of the Judicial Branch to do justice in criminal prosecutions.” [United States v. Nixon] According to the majority, however, any incursion on Executive power is too much. When presumptive immunity is this conclusive, the majority’s indecision as to “whether [official-acts] immunity must be absolute” or whether, instead, “presumptive immunity is sufficient,” hardly matters.

And then we come to the “no immunity for unofficial acts zone”. If a president were to sexually assault a woman, maybe “grab her by the pussy”, say, that would presumably be an unofficial act for which he could be prosecuted.

But even here, we run into a president’s prerogative to use his official powers to obstruct justice. Recognizing his legal exposure, a president might order federal officers to destroy evidence, or even kill the woman before she could report the crime. He might then pardon the officers who carried out this order. These would be official acts, and so completely immune from prosecution.

Chilling doom. Justice Jackson’s dissent lays out how the fundamental structure of our government has changed: The executive and judicial branches gain power and Congress loses power. The very vagueness of the current decision empowers the Supreme Court to decide what presidential behavior is or isn’t permitted.

[T]he majority does not—and likely cannot—supply any useful or administrable definition of the scope of that “core.” For what it’s worth, the Constitution’s text is no help either; Article II does not contain a Core Powers Clause. So the actual metes and bounds of the “core” Presidential powers are really anyone’s guess. … [T]he Court today transfers from the political branches to itself the power to decide when the President can be held accountable. What is left in its wake is a greatly weakened Congress, which must stand idly by as the President disregards its criminal prohibitions and uses the powers of his office to push the envelope, while choosing to follow (or not) existing laws, as he sees fit. We also now have a greatly empowered Court, which can opt to allow Congress’s policy judgments criminalizing conduct to stand (or not) with respect to a former President, as a matter of its own prerogative.

She also hints at the likely partisan applications of this power.

Who will be responsible for drawing the crucial “ ‘line between [the President’s] personal and official affairs’ ”? To ask the question is to know the answer. A majority of this Court, applying an indeterminate test, will pick and choose which laws apply to which Presidents

And finally, Sotomayor takes the long view:

Looking beyond the fate of this particular prosecution, the long-term consequences of today’s decision are stark. The Court effectively creates a law-free zone around the President, upsetting the status quo that has existed since the Founding. This new official-acts immunity now “lies about like a loaded weapon” for any President that wishes to place his own interests, his own political survival, or his own financial gain, above the interests of the Nation. The President of the United States is the most powerful person in the country, and possibly the world. When he uses his official powers in any way, under the majority’s reasoning, he now will be insulated from criminal prosecution. Orders the Navy’s Seal Team 6 to assassinate a political rival? Immune. Organizes a military coup to hold onto power? Immune. Takes a bribe in exchange for a pardon? Immune. Immune, immune, immune. Let the President violate the law, let him exploit the trappings of his office for personal gain, let him use his official power for evil ends. Because if he knew that he may one day face liability for breaking the law, he might not be as bold and fearless as we would like him to be. That is the majority’s message today.

With other safeguards stripped away, the only protection the people have is their own vote, for a long as that is allowed and recognized. We must elect only presidents of high character who will not use the “loaded weapon” this Court has provided. Because once presidents are in power, little can be done to constrain them.

[1] Here’s Slate’s Dahlia Lithwick and Mark Joseph Stern on February 6:

The question is not whether a majority will ultimately agree with Trump (it won’t) but whether a majority will abet Trump’s efforts to run out the clock (it might).

[2] The faux humility of Roberts’ opinion sometimes reads like a bad joke.

the current stage of the proceedings in this case does not require us to decide whether this immunity is presumptive or absolute. Because we need not decide that question today, we do not decide it.

In reality, the only thing the Court needed to decide is what should happen to the current indictment. Roberts’ whole opinion is a gratuitous exercise in judicial overreach. But no, after much theorizing about situations that may or may not ever occur, the specifics of this case are what get punted back to the lower courts for another yo-yo ride of decisions and appeals that can waste months or maybe years.

[3] This is where Justice Barrett leaves the conservative bloc, giving this example:

Consider a bribery prosecution—a charge not at issue here but one that provides a useful example. The federal bribery statute forbids any public official to seek or accept a thing of value “for or because of any official act.” The Constitution, of course, does not authorize a President to seek or accept bribes, so the Government may prosecute him if he does so. Yet excluding from trial any mention of the official act connected to the bribe would hamstring the prosecution. To make sense of charges alleging a quid pro quo, the jury must be allowed to hear about both the quid and the quo, even if the quo, standing alone, could not be a basis for the President’s criminal liability.

In other words, in this hypothetical bribery case, a jury could only hear about the bribe, and couldn’t be told what the president did to earn the bribe. Did he commute the last month of a dying man’s prison sentence, or did he give terrorists a nuclear weapon? Sorry, jurors, but we can’t tell you.

Barrett’s dissent has even more significance when you consider that both Thomas and Alito should have recused themselves from this case: Thomas because his wife could be a material witness, and Alito because the flags flying over his two houses raise legitimate concerns about his impartiality.

Do the math: Barrett should have been the swing vote in a 4-3 decision, and her dissent should have been the majority opinion.

[4] No one, perhaps, beyond Richard Nixon, who told David Frost “when the president does it … that means that it is not illegal.” Prior to the current case, this quote had widely been considered horrifying. Now, in most cases, it is the law.

Comments

“The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America”

The President can be removed through impeachment process or through article that now should be maybe used to remove senile Biden?

Nixon ordering watergate was not one of his official duties and he could have been prosecuted after his term or resigning but of course was pardoned.

He could have pardoned himself as can Trump which is why all these Biden & Co initiated lawsuits have been in such hurry to convict him before he is elected second time.

Presumption of innocence is present until all appeals are exhausted.

Nixon claimed that anything the President does is legal.

The House spent months and how many millions of dollars trying to find something they could accuse Biden of doing in order to justify an impeachment. They found nothing. Why would another attempt yield anything different?

Whether or not the Watergate cover up was an official duty is far from clear, and certainly not up to you or I to determine. It would be up to a court — likely a string of courts — in an increasingly corrupted judicial system. There is little doubt that had Trump done what Nixon did (which was the cover up, much more than the crime), there would be no consequences. Trump, in fact, did much worse than Nixon ever imagined and will likely walk away scott free — thanks in no small part to this corrupt and illegitimate decision.

Having failed in every judicial attempt to overturn the election, how can any further act be an “official act”?

Everyone is missing the point of this case. The president, like every other official, has always had qualified immunity for his official acts. The issue of prosecuting a former president for crimes committed while in office has never come up before, and I doubt if Trump thought ahead to “maybe I’d better not do this or I might be prosecuted.” Biden also won’t order Seal Team Six to assassinate Trump because whoopee, now he doesn’t have to worry about going to prison.

What happens now is Judge Chutkan has to rule on which counts of the indictment were “official acts” and which weren’t, and what evidence may be used to support any surviving indictments. Unless she dismisses the case in its entirety, her decision will go right back to the Supreme Court when Trump appeals it, forcing them to clarify what they meant, specifically. Or, Jack Smith will have to re-file the indictment in light of this decision. Before you know it, the election will be over and it won’t matter.

This is why SCOTUS even took the case, and why they dragged it out as long as possible.

At the beginning of the movie ‘Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,’ a stupid outlaw challenges Cassidy to a knife fight for gang leadership. Asked about rules, he declares ‘No rules in a knife fight!’ Cassidy immediately kicks him in the balls, ending the fight.

The radical Republican Supreme Court has now ruled ‘No rules in a Presidency!’ Like the outlaw, the Supreme Court will regret those words. They have enabled mayhem, revolution, and terror, and it may well touch even them in due time.

The audience loved it when Cassidy’s opponent went down. Even outlaw gangs have rules, and we rightly fear and disapprove of those who claim otherwise. But the radical Republicans now are trying to make revolution, as Roberts of the Heritage Foundation proudly calls it. Revolutions throw out the rules that would impede their seizure of absolute power. But the rules that protect us all from police state tyrrany, from official acts of terror, torture, murder? They go too. Unfortunately, Butch Cassidy isn’t around to handle the situation. We’re going to have to do it ourselves, kicking the Republicans where it counts in November.

And yet, very mysteriously, Republicans are claiming this as a huge win against Biden’s weaponization of the DoJ.

Which, you know, if it was real, would now be very explicitly immune from prosecution, being the one thing the Supreme Court’s Republican majority actually bothered to clarify unambiguously in this ruling.

The problem with being forced now to rely solely on “the vote” is that the authoritarian right has done, and continues to do, everything it can to dilute and negate the ability of a counter majority to prevail.

From gerrymandering to voter suppression to partisan takeovers of election offices to novel legal theories that claim state legislators may ignore and change the who their citizens chose as Electors, they have rigged the process to favor who the minority in control wants.

The Trump 2024 campaign (according to a new, must-read Tim Alberta story in The Atlantic) is focusing its efforts not on traditional GOTV efforts, but rather on recruiting MAGA cadres to ‘observe’ at polling locations in battleground states and legions of lawyers who will stonewall and attempt to overturn negative results in courts overseen by increasingly partisan, loyalist judges, aided by state officials working for the cause.

Why? Because they understand the truth in Stalin’s famous maxim that it’s not who votes that counts, but rather who counts the votes.

And now, a POTUS who organizes a seditious conspiracy to overturn the results of his own election so he may remain in power is immune from criminal prosecution for doing so, just as long as his lawyers make sure he cloaks his actions in the protection of “official acts”, something I’m sure John Mitchell wishes he had at his disposal when executing Nixon’s obstruction of justice.

Trump himself may be too stupid to fully appreciate the extent to which the POTUS is now unleashed. His enablers probably markedly less so. But the day will arrive when a despot comes along who is as venal and amoral as Trump, as intelligent as Biden, and as focused on total control as Hitler. And when it does, Justice Sotomayor will be acknowledged as clairvoyant.

Trackbacks

[…] the Supreme Court’s decision on presidential immunity — which (as I covered in the previous post) isn’t quite the End of the Republic by itself, but could be a significant step in that […]

[…] week’s featured posts are “The Immunity Decision: End of the Republic or No Big Deal?” and “The Biden Situation“. In this morning’s teaser, I promised a third […]