The law gives way to power and politics.

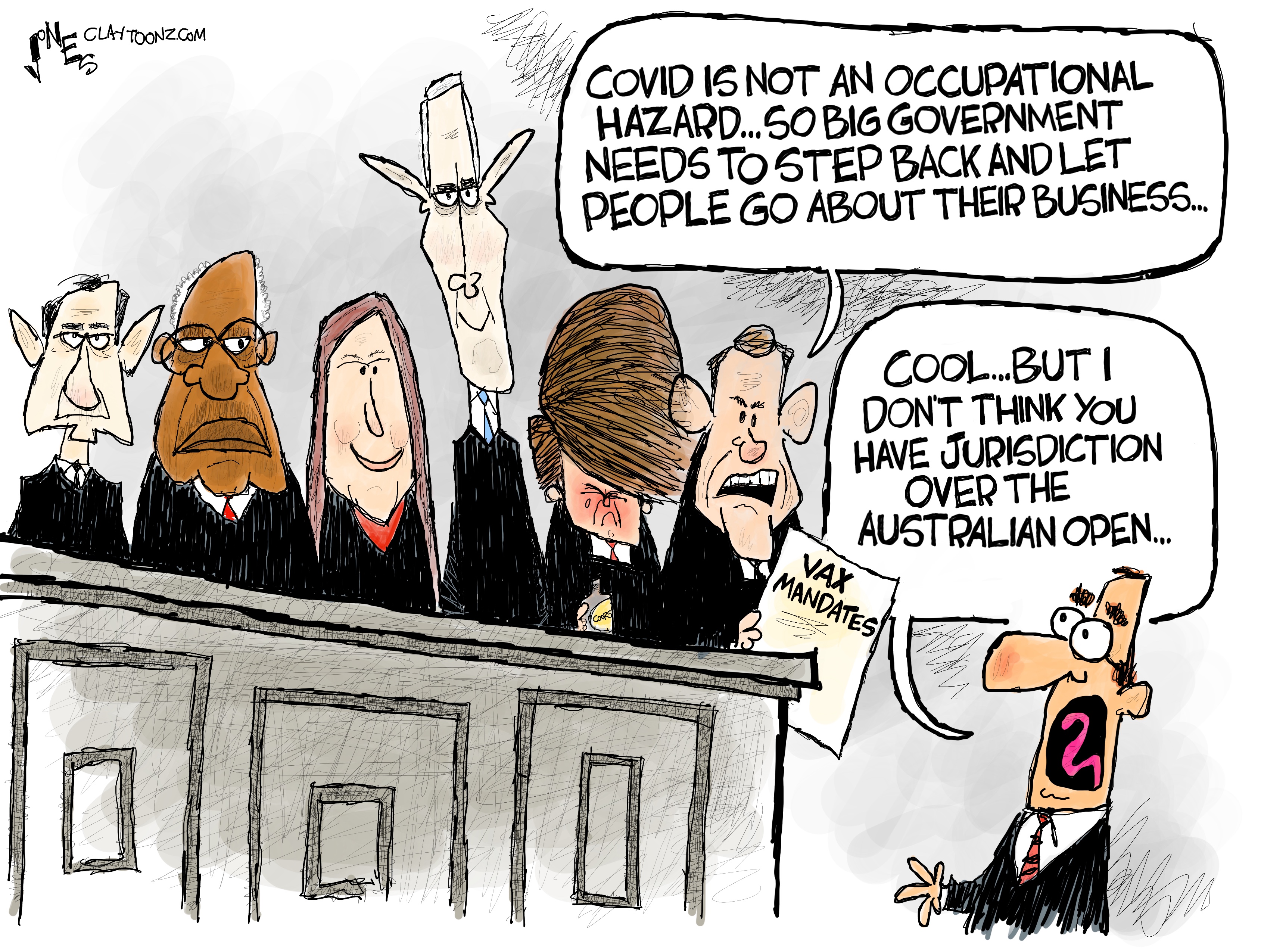

As expected, the Court nuked the Biden administration’s workplace vaccine-or-test mandate, while upholding a mandate for health care workers. The heart of the 6-3 majority’s negative opinion was this argument:

The question, then, is whether the [Occupational Safety and Health] Act plainly authorizes the Secretary’s mandate. It does not. The Act empowers the Secretary to set workplace safety standards, not broad public health measures. …

Although COVID–19 is a risk that occurs in many workplaces, it is not an occupational hazard in most. COVID–19 can and does spread at home, in schools, during sporting events, and everywhere else that people gather. That kind of universal risk is no different from the day-to-day dangers that all face from crime, air pollution, or any number of communicable diseases. Permitting OSHA to regulate the hazards of daily life—simply because most Americans have jobs and face those same risks while on the clock—would significantly expand OSHA’s regulatory authority without clear congressional authorization.

Got that? The majority doesn’t claim that Covid isn’t a hazard at work, but that you might catch Covid lots of other places too. So if you could pick up black lung disease at the supermarket, OSHA wouldn’t be able to regulate that either. The Atlantic’s Adam Serwer labels this logic “laughable”.

OSHA regulates many, many hazards that are also present outside the workplace. The fact that you can die in a fire in your apartment is not an argument against regulating fire hazards in factories or offices.

Fires, falling down stairs, handling sharp objects, etc. are all “hazards of daily life”. But while Americans can mitigate the risks we face at home, we’re mostly at the mercy of our employers at work. That’s why we need OSHA. The Breyer/Kagan/Sotomayor dissent explains:

OSHA has issued, and applied to nearly all workplaces, rules combating risks of fire, faulty electrical installations, and inadequate emergency exits — even though the dangers prevented by those rules arise not only in workplaces but in many physical facilities (e.g., stadiums, schools, hotels, even homes). Similarly, OSHA has regulated to reduce risks from excessive noise and unsafe drinking water—again, risks hardly confined to the workplace.

People like me. Let me bring this down to a personal level: My wife and I, being over 65 and having a few other complicating factors, have been very careful about minimizing our Covid risk. We haven’t caught Covid “at home” because we don’t let a lot of people into our home. We haven’t caught it “during sporting events” because we have been staying away from sporting events. And we haven’t caught it at work because we’re retired.

Until the current Omicron surge, our friends and family had almost entirely escaped infection too. How? Partly by being sensible people who take science seriously, but also because those who weren’t retired were almost all in white-collar jobs that allowed them to work from home. (I’d love to see some statistics breaking down Covid risk by education or job category.) The ones I worry most about are the few who have in-person jobs that require interacting with the public.

In short, the workplace isn’t the only place Americans can catch Covid, but it’s the primary source of unavoidable risk.

Now, if you are somebody who thinks Covid is a scam, or if you’re just “done” with trying to avoid it, the Court’s ruling makes perfect sense: You’re interacting with unmasked untested unvaccinated people all the time, so what’s the problem if you meet a few more at work? But for those of us still trying not to get sick — and especially for service-industry people who have been considering when it will be safe to re-enter the job market — this ruling is a major blow. The Court has said that our government is powerless to help us.

What the laws say. The majority’s logic is tenuous on its face, but the best argument against the Court’s opinion is to read the bleeping law, which the dissent reproduces:

OSHA ’s rule perfectly fits the language of the applicable statutory provision. Once again, that provision commands — not just enables, but commands — OSHA to issue an emergency temporary standard whenever it determines “(A) that employees are exposed to grave danger from exposure to substances or agents determined to be toxic or physically harmful or from new hazards, and (B) that such emergency standard is necessary to protect employees from such danger.”

Strangely, though, Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kavanaugh flipped to the other side of the argument in a similar case decided the same day: In a 5-4 decision, the Court let stand a different Biden administration vaccine mandate — affecting 10 million people rather than 84 million — on health care workers.

Reading that opinion (which is unsigned, but probably written by either Roberts or Kavanaugh), it’s hard to see the difference between this and the more general mandate. The regulating agency has changed (HHS rather than OSHA), and the agency is implementing a different set of laws, but the main difference is that in this case Roberts and Kavanaugh decided to take those laws seriously.

Both Medicare and Medicaid are administered by the Secretary of Health and Human Services, who has general statutory authority to promulgate regulations “as may be necessary to the efficient administration of the functions with which [he] is charged.”

One such function—perhaps the most basic, given the Department’s core mission—is to ensure that the healthcare providers who care for Medicare and Medicaid patients protect their patients’ health and safety. Such providers include hospitals, nursing homes, ambulatory surgical centers, hospices, rehabilitation facilities, and more. To that end, Congress authorized the Secretary to promulgate, as a condition of a facility’s participation in the programs, such “requirements as [he] finds necessary in the interest of the health and safety of individuals who are furnished services in the institution.”

It wouldn’t be hard to use these paragraphs as a template and fill in “OSHA” and “workers” in place of “HHS” and “Medicare and Medicaid patients”. (If anything, the law is clearer in the OSHA case.) But Roberts and Kavanaugh couldn’t support such a revision. For some reason, the “core mission” of HHS matters in a way that the core mission of OSHA doesn’t.

Vox’s Ian Millhiser observes that the two opinions are “at war with each other”, and the “The Court is barely even pretending to be engaged in legal reasoning.”

Politics. Probably the Chief Justice’s thinking has more to do with protecting the Court’s image than upholding the law.

Roberts hates to make sweeping decisions whose judicial activism would be obvious to the public. Instead, he prefers to chip away at the federal power or individual rights that he wants to destroy, in decisions that are supposed to seem moderate individually, even as they stack up to create radical change. So he invented with a novel way to uphold ObamaCare while simultaneously undercutting precedents about the Commerce Clause and allowing states to opt out of Medicaid expansion. He left the Voting Rights Act in place while tossing its main enforcement mechanism. He’s been uprooting campaign finance laws bit by bit rather than declaring outright that Money is sovereign (which is clearly what he believes).

And so in these two cases, Roberts cuts the vaccine-mandate baby into a small piece and a large piece. He does what he wants with the larger piece, while letting the law govern the smaller piece to show how moderate he is.

Expect something similar in June when the Court rules on abortion: The other five conservative justices will want to reverse Roe v Wade outright. But Roberts will want to put loopholes in Roe to allow most (but probably not all) of the Roe-violating state laws to stand, while claiming that he technically “upheld” Roe rather than reversed it.

The question then will be whether he can persuade Kavanaugh, as he did this time.

Biden’s next steps. If the Court’s complaint about a broad mandate is that it’s not occupationally specific or tied to specific risks, OSHA could respond by breaking its mandate into occupation-specific chunks or detailing a more complex set of standards that would apply to all businesses, not just those with more than 100 employees. Apparently, it already drafted such a rule, but hasn’t issued it.

OSHA’s path forward to protecting workers from Covid-19 is clear. First, the agency should take the previous OSHA standard out of the desk drawer, dust it off, update the data, make any tweaks to ensure it fits the court’s new suggestion that it be risk-based and send it over to the White House. The standard should cover all workers in higher risk jobs, not only those employed by large employers.

That might or might not work, depending on whether the Court decides to play Calvinball and make up new rules as it goes.

The radicals. One related issue I speculated about last week was whether the Court would base its vaccine-mandate rulings on a “nondelegation” argument that would hamstring not just OSHA, but federal regulating agencies generally. The six-justice majority in the OSHA case (the usual conservative bloc) hints at such sentiments, but never actually invokes them.

But Justice Gorsuch’s concurrence with that ruling, joined by Thomas and Alito, does. The OSH Act can’t authorize the vaccine requirement, Gorsuch writes, because it is a general delegation of power from Congress, not a specific response by Congress to the pandemic. The power-granting subsection the dissent quoted can’t be applied because it

was not adopted in response to the pandemic, but some 50 years ago at the time of OSHA’s creation

It’s not hard to see where this line of thinking goes: Antitrust law can’t apply to markets that were inconceivable when the Sherman and Clayton Acts were passed more the 100 years ago. The Clean Air Act is more than 50 years old; clearly the EPA can’t invoke it to ban pollutants nobody knew about then. How can the SEC regulate complex financial derivatives that the laws don’t specifically mention, and that change faster than new laws can address? (Of course, this logic will never be applied to the Second Amendment, whose authors could not possibly have foreseen AR-15s.)

In this current age of obstruction and filibuster, the ultimate result of nondelegation would be the end of federal regulations across the board. Not because anti-regulation politicians took their case to the voters, won elections, and repealed OSH, the Clean Air Act, and the rest of our regulating laws, but because unelected judges (many chosen by presidents who lost the popular vote) made the entire system of regulation unworkable, independent of whatever the American people might have wanted.

A majority of the Court isn’t there yet. But three justices are.

Comments

“The question then will be whether he can persuade Kavanaugh, as he did this time.”

A case or two of light beer oughta do it.

I laughed out loud at this comment. Well said friend.

The Supreme Court majority lied in this ruling. Full stop. How do I know? Go to their website (https://www.supremecourt.gov/) – the Supreme Court is current closed to visitors DUE TO COVID. Obviously, Chief “Justice” Roberts considers COVID an occupational hazard or he wouldn’t have closed the Supreme Court. The fact that he won’t extend that courtesy to the many workers who have kept his sorry self alive and fed is evil.

The Government’s Advocate should have ripped his mask away at the Majority’s Reading !

@julianuniversalist Your reading of this lie rests on the justices viewing their positions as “jobs” and the Supreme Court building as a “workplace”. It’s quite clear from their behavior that this is not the case for at least the 6 Republican justices. A job would imply some service the court were providing, that the court were just one cog in the machine of governance. What the court is actually doing is much more akin to royal decrees. The Republican justices understand the mandate from their key benefactors to act as sovereign overlords of the law, and thus have ascended beyond the purview of a word such as “job”. Jobs are things for the masses in any case, and the protections applicable to employees only matter when the higher powers are under attack by the common people, hence the court’s closing.

It is also worthwhile to note that besides “homes” the rest of the places where people catch covid are workplaces. People work at stadiums, on busses, in schools, in hotels. These are the “essential workers” that we are pressing into service all while claiming they’re too worthless to pay well.

Trackbacks

[…] This week’s featured posts are “Merrick Garland Starts Getting Serious” and “The Court and the Vaccine Mandates“. […]