Should the economy be organized to benefit producers and consumers, or a few big middlemen? We’ve been answering that question wrong since Ronald Reagan, and we’re about to do it again.

Should the economy be organized to benefit producers and consumers, or a few big middlemen? We’ve been answering that question wrong since Ronald Reagan, and we’re about to do it again.

The FCC, with its new Republican majority, is proposing to end the era of net neutrality. If you’re some kind of internet nerd, you probably already know exactly what that means and have had a strong opinion about it for a long time. If not, though, it probably sounds like one of those intense debates nerds often have about mysterious topics like databases or user interfaces: You have no idea what they’re talking about, you don’t bother to find out, and whatever results from the argument, it never seems to bite you.

This one is going to bite you. When the bite comes, it might arrive in a form you won’t easily connect back to this decision. But it is going to bite you. It’s going to bite the whole economy.

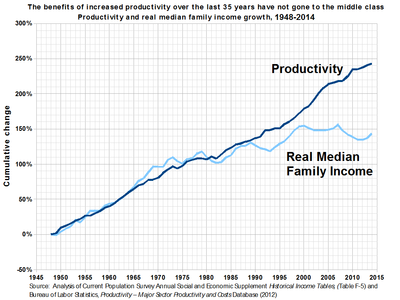

To explain how and why, let me detour through a subject you probably do care about: economic inequality. Here’s a graph I keep posting in one form or another, because I think it points to the most significant fact in American politics: Up until around 1980, median income closely tracked productivity. And then something happened to disconnect them. Productivity kept increasing, but median income stagnated.

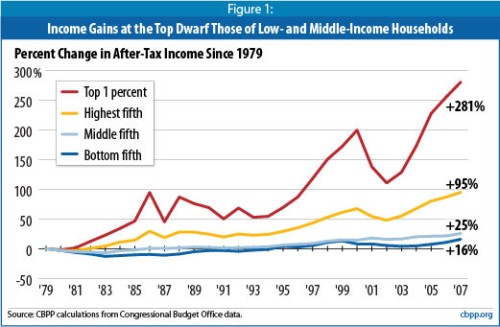

Unsurprisingly, this has led to a concentration of income at the top: The people who make wages have lost ground, while the people who pay wages have gained.

Unsurprisingly, this has led to a concentration of income at the top: The people who make wages have lost ground, while the people who pay wages have gained.

And the greatest concentration has been at the very tip-top: The share of wealth held by the top tenth of a percent has reached levels not seen since the Great Depression.

And the greatest concentration has been at the very tip-top: The share of wealth held by the top tenth of a percent has reached levels not seen since the Great Depression.

So what happened in 1980? The facile answer is that Ronald Reagan was elected president. But that explanation is too simple, because a president doesn’t deal out national wealth like a deck of cards. What did Reagan do, if anything, that touched off this new Gilded Age of concentrated wealth?

So what happened in 1980? The facile answer is that Ronald Reagan was elected president. But that explanation is too simple, because a president doesn’t deal out national wealth like a deck of cards. What did Reagan do, if anything, that touched off this new Gilded Age of concentrated wealth?

Again, there’s a too-simple answer: He cut taxes on the rich, and he broke unions. Those actions certainly did help the wealthy and harm the middle class, but they’re not enough to explain what happened. If that were all he did, subsequent presidents should have been able to undo it.

To really understand the Reagan impact, you need to apply David Graeber’s definition of a successful revolution: Reagan changed the political common sense of his era in a way that has stuck ever since. Since Reagan, one of the basic debates in American politics has been framed as Freedom vs. Regulation, with a corollary debate of Productivity vs. Regulation. In each case, Regulation was framed as the wrong side to be on: It limits our freedom and strangles our productivity.

The result has been a completely reshuffled economy, which I first started discussing in a 2012 post “Monopoly’s Role in Inequality“.

[M]arkets are created by rules, and the rules can be structured to favor either the ends (producers and consumers) or the middle. Producers and consumers benefit from transparent markets, where the rules force middlemen to treat everyone more-or-less the same.

But markets can also be structured to give middlemen as much freedom as possible. The most profitable way to use that freedom is to create choke-points where a toll can be extracted or one producer can be played off against another. In an opaque market, the way to get rich is not to produce things, but to build middleman power that allows you to dictate terms up and down the supply chain.

What we have today, after nearly 40 years of freedom-for-the-middleman de-regulation, is an economy full of choke points. The path to vast wealth is not to make something people want (as Henry Ford made cheap automobiles) or to discover something people need (as J. Paul Getty and H. L. Hunt found oil), but to insinuate yourself between producers and consumers, create a monopolistic choke point, and charge tolls.

WalMart and Amazon, for example, are choke points; if you want to sell a product to the general public, you have to deal with them on their terms. Visa and MasterCard are choke points; retailers need them, and have to pay whatever fees they set. Cable companies are choke points; creators of TV shows can’t reach viewers without them. Google is a choke point; if you’re hoping to get around WalMart and Amazon by selling over the internet, your website needs to show up when people search for your type of product. [1]

The upshot is that post-Reagan America is no longer a place where you can build a better mousetrap and expect the world to beat a path to your door. Instead, you build the mousetrap, and then you pay off the owners of the choke points between yourself and the mousetrap-buying public. Maybe some small profit will be left for you and maybe it won’t, but the choke-point owners will do well. [2]

There are a few things worth noticing about this situation:

- In the short run, the choke-point owners often look like the good guys. Amazon has low prices; Visa gives you cash back. Middlemen often temporarily align with consumers in order to gain more power over producers. But the pattern of all monopolists remains: Once power is consolidated, it will encroach in both directions.

- We all need producers. You’re not just a consumer who spends money, you need to make money too. And since ordinary people have no chance of owning their own choke points, most of us have to make money by finding a place on the productive side of the economy, by participating in the delivery of some good or service. Choke points stop middle-class people from moving up by starting their own businesses, and they siphon money away from the kinds of productive businesses that hire people.

- “Freedom” can be anti-productivity. Given the prevailing post-Reagan political common sense, that sounds like a contradiction, but it really isn’t. If middlemen have freedom to play producers off against each other and keep the lion’s share of profits for themselves, then more of the economy’s investment will be in middlemen, and less in producers. Conversely, regulations that limit the power of middlemen are pro-productivity.

Now let’s get back to net neutrality: The point of net neutrality regulations is to control middlemen who own a major chunk of our economic infrastructure: the internet service providers like Comcast, Verizon, and AT&T. Once they’re freed from regulation, you can expect them to set up choke points and charge tolls. (This is how it works in Portugal.)

If you provide some service over the internet, for example, you will find yourself competing for the favor of ISPs rather than consumers. Maybe Netflix will pay Verizon so that its streaming service comes in faster and with higher quality than Amazon Prime; or maybe Amazon will outbid it. [3] In either case, the new revenue stream for Verizon either means higher prices for consumers or less spent by Amazon or Netflix on new content. It’s basically just a wound through which Verizon can suck blood out of the productive economy.

Wired suggests that we guess how the ISPs will use this power by looking at what they already do in data-limited plans:

When AT&T customers access its DirecTV Now video-streaming service, the data doesn’t count against their plan’s data limits. Verizon, likewise, exempts its Go90 service from its customers’ data plans. T-Mobile allows multiple video and music streaming services to bypass its data limits, essentially allowing it to pick winners and losers in those categories.

Consumers will likely see more arrangements like these, granting or blocking access to specific content … Net neutrality advocates have long worried that these sorts of preferential offerings harm competition, and by extension, consumers, by making it harder for smaller providers to compete. A company like Netflix or Amazon can likely shell out to sponsor data, but smaller companies don’t necessarily have the budget. … the future internet, then, could look a more extreme version of today’s mobile plans, with different pricing tiers for different levels of video quality for different apps. That means more customer choice, but perhaps not in the way anyone actually wants.

In the conservative fantasy world, the toll collectors will use some fraction of their windfall profits to improve their broadband networks (just as corporations in general will generously use their Trump tax cuts to hire more workers and pay them higher wages). In reality, though, it will be one more opportunity for parasites to latch on to the productive economy. The parasites will do well; ordinary people, not so much.

[1] Apple is an interesting hybrid. It makes things people want, like iPhones. But it too sees how the post-Reagan economy works and wants to evolve into a choke-point company. Already, its App Store is a choke point for software builders, iTunes is a choke point for music producers, and it would like ApplePay to become a choke point upstream from Visa and MasterCard.

[2] A choke point I face on this blog is Facebook. Three years ago, Facebook’s algorithms allowed posts on no-name blogs to go viral. (2014’s “Not a Tea Party, a Confederate Party” got more than half a million hits.) Now that’s much harder. (2017’s most popular Sift post has less than 4,000 hits.) Meanwhile, I’m constantly bombarded with suggestions that I should pay Facebook to get more visibility. I suspect Google does something similar to video bloggers on YouTube.

The analogy isn’t quite perfect, because I’m not trying to make money off my readers. But Josh Marshall at TPM is trying to make money, in an environment he described recently as a “digital media crash“. The situation was tough to begin with, and then …

Then came the platform monopolies: Google, Facebook and a few others. Over the last five years or so but accelerating rapidly in the last 24 months, they’ve gobbled up almost all of the growth in advertising revenue and begun to engross a substantial amount of the existing advertising revenue as well.

That increased flow of money to the platform monopolies takes it away from the actual journalists who find out things and explain them to you.

[3] One article endorsing the FCC proposal points to the ambiguous role of choke-point giants like Amazon and Google.

Net neutrality’s dubious value is made obvious by the misleading way Democrats and many news outlets reported the decision. “F.C.C. plans net neutrality repeal in a victory for telecoms,” wrote the New York Times. Missing from the headline or lede was that the decision was a loss for Netflix, Amazon, Google, and other corporate giants that provide content.

The logic of this should be obvious: Amazon and Google are on the side of the general public on this issue, but for their own reasons: They don’t want new choke points to be constructed upstream from their choke points.

Comments

The original rationale for the imposition of public-utility-style regulation in the late 1800’s was that “middlemen” — in the early case, the owners of grain silos — “stood at the gateway of commerce and take the toll of all who pass.”

As this article establishes, choke-point toll collection is precisely and literally the position of internet service providers in today’s world.

The key question going forward is worrisome, however. If the FCC caves on net neutrality — as it is likely to do — are courts likely to impose the duty to administer a regulatory scheme on an unwilling regulator? Frankly, given the traditionally limited role of the judicoary, I doubt it.

Grain silos … great historical point.

This is a good review of net neutrality.

Russ http://usctrojanforce.com

One reason why Canada has very strong net neutrality rules is that one of the big telecoms blocked traffic to their subscribers to a website in support of their striking workers.

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/telus-cuts-subscriber-access-to-pro-union-website-1.531166

The outrage led to the strong bipartisan support for net neutrality in Canada.

Micheal Giest (law professor at Ottawa U) has a great write up on Net Neutrality in Canada.

http://www.michaelgeist.ca/2017/07/toward-open-innovative-internet-lies-behind-canadas-net-neutrality-success-story/

This dynamic may also contribute to the high cost of health care and education. Health insurance companies and universities seem to have grown beyond their intended purpose of connecting doctors to patients and professors to students, and are making money by being necessary rather than efficient. Is that is a sound analogy?

Insurance companies provide insurance. I don’t believe their “intended purpose” was ever to “connect” patients (whom they insure) to doctors (who they don’t). Doctors can choose to accept a person’s insurance as part or all of the payment for services they render … or not.

Yeah, the old freedom of choice argument; it just ain’t so. How long can a doctor stay in business if he refuses to see patients at the rates that Blue Cross-Blue Shield will pay? The economic pressure is so enormous that your “freedom of choice” argument rings hollow.

No. But it will take me a bit (maybe a day) to put a complete response as to why

Universities first. Universities are expensive because the primary cost of universities is labor and there is little capital can do to expedite that process. Professors are needed to both advance the fields they’re working in and teach the students. While there are loads of people complaining about University capital expenditures (new buildings etc) the main reason for this is simply capacity and in comparison to the overall budget its not a significant portion.

In a non-labor primary field you’ve got increasing productivity to negate a lot of the costs. If you’re selling shoes machines make it cheaper to make a pair of shoes and the cost in terms of labor for the shoes goes down while the price of labor (should) increase to match the higher productivity. Those shoes go to a retail store and then you buy them. The price goes up, but not as fast as wages because there are two components of the cost.

But for Universities its basically just people.

Health Care on the other hand is a combination of two economic issues. The first is an asymmetric information problem. Regular people are not doctors and are so not equipped to make decisions about what is best for their health. The second is a fundamental problem of insurance markets. Which is probably best described by a famous paper called “A market for Lemons” which discusses cars but the concept is the same. It proposes that there is a critical point where if the proportion of lemons to good cars is too high, people cannot buy a car without expecting it to be a lemon, and so the only people who sell cars are those with lemons. Same thing happens in health insurance. If only sick people buy health insurance then insurance companies have to increase the price. Increasing the price means fewer healthy people buy insurance…

Theoretically you can work a proper health insurance system but because the people with the greatest need for insurance are those with the least money (since they are least able to afford a negative shock) its always going to have to be tightly regulated.

In addition to Reagan’s contribution to changing the conversation, those Middlemen-with-choke-points-and-tolls can contribute huge sums of money to political campaigns – to help ensure that laws get written the way that they want them written. Consumers/voters get WAY out-spent.

This is one more example of why we need to change the way that we fund political campaigns.

The New York City council uses a matching program for small dollar donations to give candidates an option that doesn’t require big donors:

(https://youtu.be/4C4wGHfL_a4) and (https://www.brennancenter.org/publication/small-donor-matching-funds-nyc-election-experience).

There are two important distinctions not made here.

1) whether or not the service in question is a natural monopoly

2) whether or not the service provides tangible good

The first is important because if a “choke point” isn’t a natural monopoly you can build a better service to get around them. White there are ways to sustain a monopoly in these situations it puts a limit on the amount. More or less the threat of competition will reduce prices.

The second is important because “how companies make money” has always been important. Advertising is a valuable good. Warehousing is an efficient way to distribute goods. Companies which are doing something like so may cause others to go out of business but it’s generally not an overall loss.

Comcast et al are natural monopolies because it only ever makes economic sense to have one network in an area. You would have to duplicate much of the net in order to get around them. Facebook is a natural monopoly because network effects preclude competition. Amazon is not, you can shop online anywhere (until NN is gone). Google is not, you can provide a better search engine then you can offer alternate advertising solutions.

A good example for a company trying to do what you’re looking at but isn’t in a natural monopoly situation and doesn’t provide better service is Uber

The goal of Uber is to become a monopoly in livery. But in order to do so they have not created any efficiencies in the core model, IE the cost of driving a car to another location, but are simply subsidizing rides. Fortunately because of the second point Uber will fail, but it’s a better example of the predatory behavior you’re describing compared to Amazon and Google or Walmart

An addendum and another example of a middleman company that really does create value, even if they’re effectively becoming a monopoly.

Steam is a product of Valve. Its a digital distribution service for computer games. It has a storefront and its own application which provides DRM to producers. It allows purchasers to download their games whenever they want wherever they want(more or less). It was born out of the internet boon when Valve decided that they did not want to publish in the traditional way. Originally Steam was only a method to purchase Valve games.

However they opened the platform up to any developer who wanted to sell on their service. The fees that steam charges are low compared to traditional publishers (this is because of lower costs per copy as well as an easy platform for production) and as a result Steam has replaced traditional publishers as a means for publishing. It also has meant that there have been copies. Steam has competition in GoG as well as EA’s origin but they’re clearly the largest game in town.

These types of things aren’t examples of market failure like Comcast et al are even if it looks like one player is gobbling up the market they still have to provide a valuable service lest they be pushed out by someone who does it better.

Trackbacks

[…] Muder wrote an excellent post on today’s The Weekly Sift about how the Federal Communications Commission’s proposal […]

[…] This week’s featured post is “The Looming End of Net Neutrality (and why you should care)“. […]

[…] The Looming End of Net Neutrality (and why you should care) […]

[…] The Looming End of Net Neutrality (and why you should care) […]

[…] The Looming End of Net Neutrality (and why you should care) […]