Trump’s protectionist overreach shouldn’t send Democrats back to neo-liberalism and free trade.

I’m guessing you know the basics of this story, because it’s gotten blanket coverage in the media: Trump announced wild and ridiculous tariffs, global markets crashed, and then he partially backed off, leading to a partial recovery. (If you want a more complete review, it’s in footnote [1].)

Of course Trump never admits a mistake, so the party line is that he meant to do this all along; the whole fiasco is a negotiating tactic straight out of The Art of the Deal. And the Trump-worshiping chorus immediately fell into line: “an absolutely brilliant move“, “brilliantly executed“.

But anybody with their eyes open saw this episode for what it was: a colossal blunder that is far from fixed even now. Jay Kuo summarized: “Trump screwed up bigly on tariffs, and he knows it.” [more critiques, including mine, in footnote 3]

But even more interesting, I think, were articles defending Trump’s tariffs sort of. Typically the headlines were Trump-friendly, like “There’s a Method to Trump’s Tariff Madness” and “Stop Freaking Out, Trump’s Tariffs Can Still Work” in the NYT, or even “Tariffs Can Actually Work, If Only Trump Understood How” in the Financial Times. But the content of the articles was less favorable, more along the lines of: Higher tariffs might work, but not like this.

The best such article I found was Ross Douthat’s interview with Oren Cass (author of the “Stop Freaking Out” article). I’m not usually a big Ross Douthat fan, but here he asked the right questions and got significant nuance out of Cass.

Cass begins with a critique of the globalization era, arguing that while GDP has increased just as economic theory says it should, GDP doesn’t tell the full story.

when we’re looking at the actual well-being and flourishing of the typical working family and their ability to achieve middle-class security, we’ve seen real decay. And I think that explains why somebody like Donald Trump has become as successful politically as he has.

It’s striking how closely this echoes what Pete Buttigieg told Jon Stewart:

The bottom line is: If the economy and the government were working the way it should for most Americans, a guy like Donald Trump and a movement like Trumpism would not have been possible.

Cass notes the bifurcation between types of working people.

When you’re looking at these household income numbers, it’s important to notice how much they rely upon the household having two earners and how much more reliant they find themselves on government programs than in the past. … I think we have a problem, particularly for the right of center that sold this idea of a rising-tide-lifts-all-ships model and we all march forward together into the brave new future. What people are seeing instead is that some people got to march ahead into the brave new future and a lot of folks did not. … Research at very optimistic groups like the American Enterprise Institute shows that young men ages 25 to 29 are earning the same or less than they would’ve been 50 years ago. And I think it’s hard to sell that as a successful economy or one that’s likely to produce a flourishing society.

The conversation shifts to trade, and the corresponding loss of manufacturing jobs. Douthat asks the right question: What’s so special about manufacturing jobs? If the pay is the same, why should we care whether people work in a Ford plant or in a bank?

Cass has a set of answers:

- Manufacturing jobs tend to be scattered throughout the country, while service jobs cluster around big financial centers. So loss of manufacturing has impoverished large sections of the country, particularly small towns in otherwise rural areas.

- An economy with both manufacturing and service jobs has employment opportunities for a broader talent pool than a pure service economy has.

- Our country is more secure militarily if we manufacture the products we need to defend ourselves (rather than depend on, say, Taiwan for our advanced computer chips; depending on a potential enemy like China is even worse). But it’s hard to preserve those industries in isolation, rather than as part of a diverse and robust manufacturing sector. “If you actually want to be an industrial power, you need the actual materials themselves. You need to know how to make the tools that make the materials, things like machine tooling, the actual excellence in engineering that’s going to lead to efficient production.”

His prescription is more nuanced than either Trump’s or the free traders’.

the equilibrium you’re headed toward is not one where we shut off trade. It’s one in which there’s more friction in trade, so that there’s a preference for domestic manufacturing

So he favors the across-the-board 10% tariff. That’s not high enough to bring back low-productivity manufacturing jobs, which is probably not a worthy goal anyway. If a t-shirt made in Indonesia now imports wholesale for $2.20 rather than $2, you’re not going to start making them in Mississippi. And because trade continues, that 10% tariff does raise revenue, but not enough to replace the income tax. It’s friction, not a locked door.

Higher country-specific tariffs might be used as negotiating tools against countries that have truly unfair trading practices. But the mere existence of a trade deficit doesn’t imply unfair practices.

And finally, he sees China as a special case. Because it is our main rival for global power, we can’t let ourselves depend on them for anything really important. So higher tariffs on Chinese imports make sense, but in concert with our allies, rather than fighting a one-on-one trade war.

we want to have a large, U.S.-centered economic and security alliance. We want to have very low tariffs within that group, obviously Mexico and Canada, obviously other core allies.

But unlike in the past, we have some demands. We want to see balanced trade within that group so that we reshore and reindustrialize significantly in this country, and we want to see a common commitment among all these countries to decoupling from China.

That’s the substance of his proposals, but he also makes an important point about how they would be implemented. The purpose of tariffs is to change long-term behavior, not to create short-term shocks to the system that might drive the world economy into recession or worse. It’s more important that corporations, governments, and other key decision-makers know what tariffs will be two and three years down the line than that significant change happen right away.

That means:

- gradually phasing in higher tariffs over time

- justifying those tariffs as part of a coherent strategy

- building a consensus around that strategy — in particular getting them passed into law by Congress — so that decision-makers will know they won’t change every time the political winds shift

What we have instead — sudden tariff shocks based on the whims of one man, who might change his mind tomorrow — is all cost and little benefit.

Cass represents American Compass, a conservative think tank. But the substance of his proposals is not far away from the ideas of the Democratic left. To me, this suggests the possibility of bipartisan consensus on policy — if we could get Trump out of the way.

[1] A somewhat longer version of the story: Trump announced massive tariffs on April 2. World stock markets [2, a footnote to a footnote] spent a week crashing (with a temporary rally on April 8 when it was rumored he would back off), and then on April 9 he announced he would delay enforcing most of the tariffs for 90 days to allow the targeted countries to negotiate. However,

Trump said he would raise the tariff on Chinese imports to 125% from the 104% level that took effect at midnight, further escalating a high-stakes confrontation between the world’s two largest economies. The two countries have traded tit-for-tat tariff hikes repeatedly over the past week.

Trump’s reversal on the country-specific tariffs is not absolute. A 10% blanket duty on almost all U.S. imports will remain in effect, the White House said. The announcement also does not appear to affect duties on autos, steel and aluminum that are already in place.

The 90-day freeze also does not apply to duties paid by Canada and Mexico, because their goods are still subject to 25% fentanyl-related tariffs if they do not comply with the U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade agreement’s rules of origin. Those duties remain in place for the moment, with an indefinite exemption for USMCA-compliant goods.

Then he announced a change that seemed designed to benefit Apple and its users.

On Friday night, the US president handed Apple a major victory, exempting many popular consumer electronics. That includes iPhones, iPads, Macs, Apple Watches and AirTags. Another win: The 10% tariff on goods imported from other countries has been dropped for those products.

The partial reversal on tariffs led to a partial stock-market recovery: The S&P 500 was at 5670 when the tariffs were announced, fell to just under 5000 at its low on Tuesday, and bounced back to 5363 by the end of the week, a net fall of about 5.4%

[2] If you want to get into the weeds, apparently the crash in the bond market had more influence on Trump. The Atlantic’s Rogé Karma explains why this was so unnerving:

Yesterday morning, the U.S. economy appeared to be on the verge of catastrophe. The stock market had already shrunk by trillions of dollars in just a few days. Usually, when the stock market falls, investors flock to the safest of all safe assets, U.S. Treasury bonds. This in turn causes interest rates to fall. (When more people want to buy your debt, you don’t have to offer as high a return.) But that didn’t happen this time. Instead, investors started pulling their money out of Treasury bonds en masse, causing interest rates to spike in just a few hours.

Suddenly the entire global financial system appeared to be at risk. If U.S. Treasuries were no longer considered safe—perhaps because the country that issues them had recently shown its willingness to tank its own economy in pursuit of incomprehensible objectives—then no other asset could be considered safe either. The next step might be a rush to liquidate assets, the equivalent of a bank run on the entire global financial system.

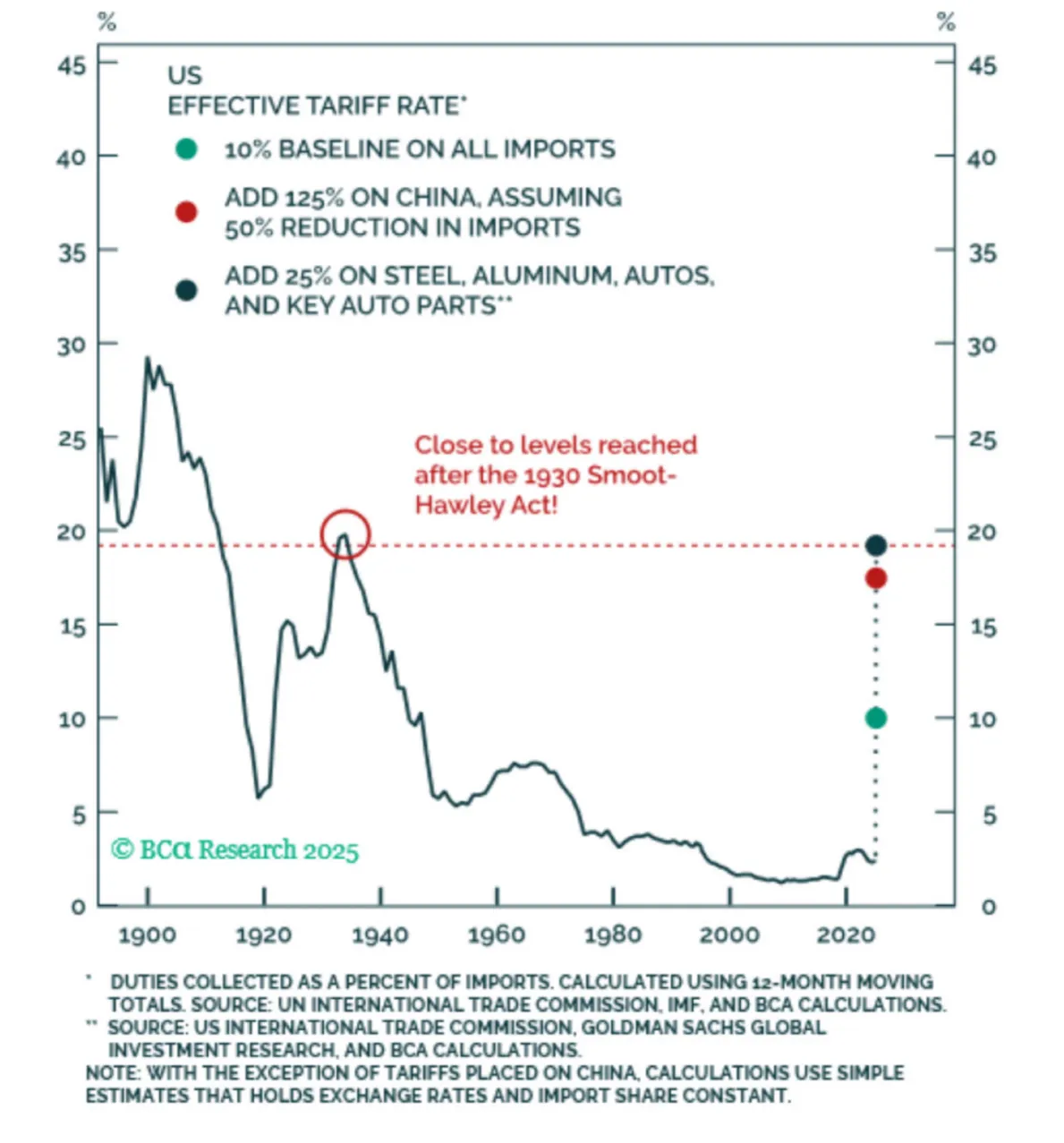

[3] Jay Kuo also provided this chart showing just how high the average tariffs are, even after Wednesday’s walk-back.

Paul Krugman posted his assessment yesterday:

I wanted to put up a quick response to yesterday’s sudden move to exempt electronics. What you need to know is that it does not represent a move toward sanity. On the contrary, the Trump tariffs just got even worse.

Main reason: The current tariff breakdown discourages US manufacturing.

Import Chinese battery: 145% tariff

Import Chinese battery inside Chinese laptop: 20% tariff

Import Chinese battery inside Vietnamese laptop: 0% tariff

I’m putting my own critique of Trump’s tariffs in this footnote, because I’ve posted it before and don’t want to get repetitive. Basically, Trump touts his tariffs as accomplishing three contradictory purposes:

- raising revenue that can replace other taxes, especially the income tax

- creating jobs by bringing manufacturing and manufacturing supply chains back to America

- motivating negotiations that will lower other countries’ barriers against American exports

To provide a revenue stream that can replace other taxes, the tariffs have to last for years and the US has to continue importing tariffed products. But to the extent that manufactured products and their supply chains move to the US, imports of tariffed products will fall, lowering revenue from the tariff.

In order to move manufacturing and its supply chains back to the US, the tariffs again have to last for years. Corporations will only move their factories if they expect the tariffs to remain in place into the distant future. But if the tariffs are a bargaining chip to be negotiated away, they won’t last. To the extent that corporations expect trade negotiations to succeed, they’ll leave their factories overseas.

Worse, the on-again/off-again nature of Trump’s tariffs, at least so far, discourages businesses from making plans that rely on those tariffs. So even if they last far into the future, they may not bring jobs back to the US. In many ways, the erratic policy we have seen the worst of all worlds.