The government can cut healthcare spending if it tempts people into gambling with their lives.

The longest government shutdown in American history came down to one issue: healthcare. Republicans have been persistent about dismantling the ObamaCare model, claiming that they have a different approach that will yield better care for less cost. And so the subsidies that kept policies on the ObamaCare marketplace affordable have been allowed to lapse for 2026 policies. Democrats tried to reverse that as a condition of reopening the government, but appear to have failed.

Of course, Trump has been promising to spell out a “beautiful” healthcare plan since 2015, and we’ve still seen nothing. Critics say Republicans don’t really have a plan, which is true in the sense that they don’t have a written piece of legislation that can be compared to the Affordable Care Act, apples to apples. (They also have nothing that could take effect in time to replace the 2026 ObamaCare policies they have now made unaffordable for millions of Americans.) Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene makes an even stronger claim, that even within the Republican House conference, Mike Johnson has not yet presented “a single policy idea”. Speaker Johnson counters that Republicans have “pages and pages and pages of ideas of how to reform healthcare”, and has pointed to a report the Republican Study Committee wrote in 2019.

It’s natural and probably appropriate to be cynical about that claim, but for a few minutes let’s take Speaker Johnson seriously. What’s in that report? It’s 58 pages, most of which are spent criticizing ObamaCare. But it does get around to presenting some ideas on pages 32-50: things like health savings accounts, allowing a wider range of choices in insurance, changes to the way employer-paid premiums are taxed, and so on — enough individual notions to get you confused about the overall picture. But basically it comes down to this: They want you to gamble with your life and health.

In order to understand their proposals, let’s lay out the context: starting with the pre-ObamaCare situation, then what ObamaCare did, and then the ways Republicans have broken ObamaCare since.

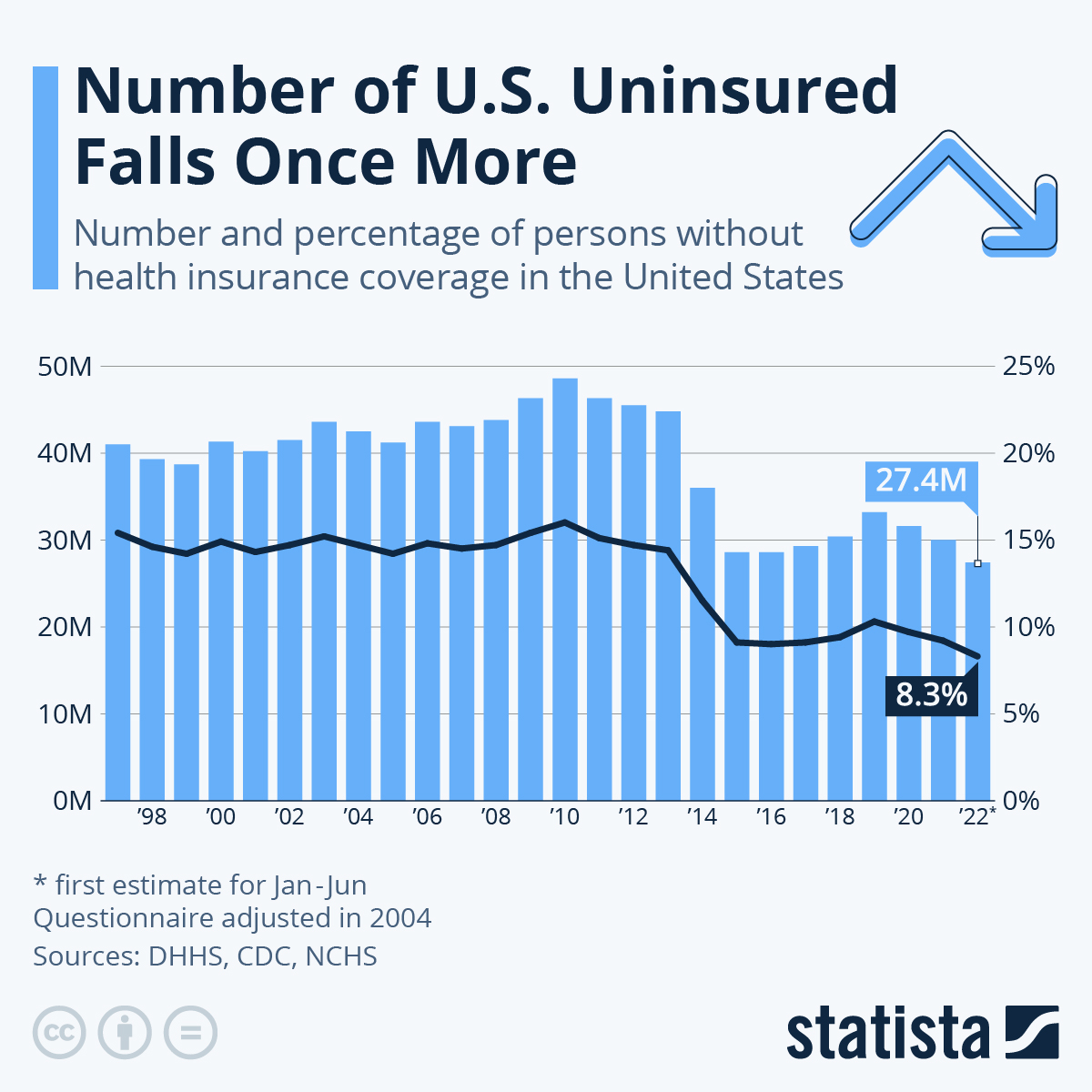

Before ObamaCare. When the Affordable Care Act was passed in 2010, about 16% of Americans — 48 million in all — did not have health insurance, and the number was growing every year. Tens of millions of others (the exact number depends on your definitions) had some form of “junk insurance” — a policy that worked just fine for relatively minor things like a broken arm, but would leave you in a lurch if you developed some really expensive condition.

People were uninsured for a variety of reasons: Some couldn’t get insurance because they had pre-existing conditions like cancer or heart disease that made them bad risks. Others were young and healthy and saw no reason to pay significant amounts of money for care they believed they would never use. (I did this myself at age 21 in the summer between my undergraduate and graduate-school coverage. Looking back, I feel foolish about that gamble, but I got away with it.) For others, health insurance had to compete with rent and food for their limited resources. Or perhaps their health was not so bad as to make them uninsurable, but bad enough that the rates they were offered were astronomical.

Junk insurance came in a variety of forms. Maybe, if you had survived some expensive illness like cancer, it would specifically exempt any condition related to a return of that illness. Maybe it would have an annual or a lifetime cap on what it would pay out. (If you had a debilitating disease like MS, or a child born with significant birth defects — as my college roommate did — you might go over that lifetime cap in just a few years. Then you’d be uninsurable.) Maybe it would have to be renewed every year or two, giving the insurance company a chance to drop you if it wasn’t making money on your policy.

In short, somewhere between 1/4 and 1/3 of Americans lived with the worry that if they needed significant medical care, they wouldn’t be able to pay for it.

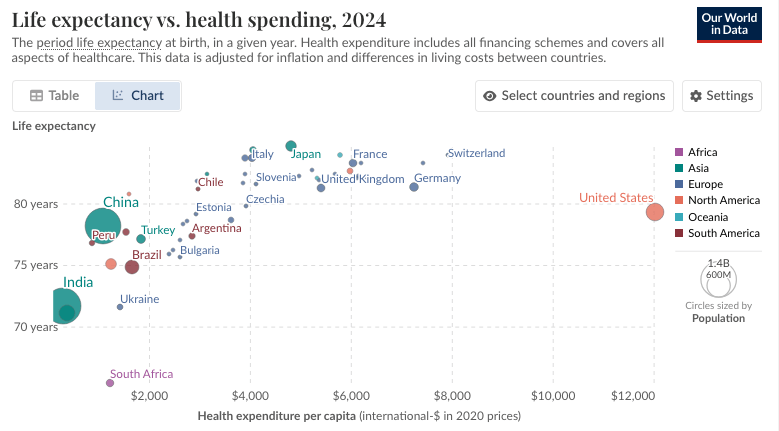

The roots of ObamaCare. This healthcare anxiety is a uniquely American problem, because other rich countries don’t regard medical expense as a personal responsibility, and instead pay for it through some national system. Statistics argue in favor of that approach: Among wealthy nations, the US stands out both for its per capita spending on health care, and for its low life expectancy. So we pay more, but get worse results.

But national healthcare is “socialism”, which is anathema to American conservatives. So in an attempt to stop the US from opting for a European-style national health system, the conservative Heritage Foundation created a different model in a 1989 report. The basic idea was that you achieve 100% coverage through a private-insurance system by

- mandating that individuals have insurance

- forcing insurance companies to cover everybody who wants their coverage

- subsidizing insurance for those who can’t afford it

That model was the basis for the RomneyCare plan that Massachusetts adopted in 2006 under Republican Governor Mitt Romney. RomneyCare in turn begat ObamaCare in 2010.

So this is an important thing to understand about the politics of healthcare: Republicans have had a hard time coming up with a healthcare plan because Obama stole their plan. He left them with a difficult choice: They could have declared victory, but that would have meant joining forces with the Black guy in the White House, which was unimaginable.

I have occasionally wondered how Mitt Romney would have fared in 2012 if he could have run on his record as the Father of ObamaCare and general solver-of-impossible-problems. But this was not to be.

What Obama did. In addition to the Heritage Foundation’s mandate-and-subsidize idea, Obama and Romney recognized the patchwork way that most Americans were already covered: If you were old, you had Medicare; if you were poor, you had Medicaid; children got covered under CHIP; veterans had the VA; people with good jobs got coverage through their employers. American healthcare was like a big bed with a lot of small blankets that covered most people, but not everybody.

So a second fundamental idea of ObamaCare was to make the blankets bigger: Insist that companies employing more than 50 people full time had to offer health insurance, expand Medicaid so that it covered the working poor as well as the destitute, and so on.

Even the bigger blankets wouldn’t stretch to cover everybody, so the ObamaCare exchanges were created: marketplaces where individuals could buy their own policies, without regard to their previous health record, and with a sliding scale of subsidies depending on income.

The mandate-and-subsidize system only works if the term “insurance” actually means something, so ObamaCare also defined what private insurance had to cover. In particular, this made junk insurance illegal. Annual and lifetime caps were gone, as were provisions not to cover certain common problems. Many people who had junk insurance didn’t realize the risks they were taking, and resented the fact that their cheap policies were now illegal. This is how Obama’s claim that “If you like your plan you can keep” got picked out as the Lie of the Year for 2013. (Personally, I liked my employer-provided insurance, and I kept it.)

And it all sort of worked. As you can see in the graph above, the number of uninsured began to drop after 2010, dropped more when the exchanges came online in 2014, and didn’t start rising again until Republicans began breaking the system during the first Trump administration. And these numbers don’t give the ACA credit for the number of people whose junk insurance was replaced by real insurance.

How Republicans have sabotaged ObamaCare. Republicans have tried to repeal the Affordable Care Act again and again ever since it was passed — at least 63 times in all. Their effort always foundered on the same point: Repealing the ACA would instantly create about 20 million uninsured Americans, and the Republicans had no plan for dealing with them. The closest they came was in 2017, with the slogan “Repeal and Replace”, where the “replace” half was always left vague. That vote came down to John McCain’s famous thumbs-down moment.

But failing to repeal didn’t mean failing to sabotage. The most obvious bit of sabotage was the ultimately successful attempt to end the individual insurance mandate, which assessed a penalty on people who went uninsured. At first they tried to undo it through the courts, and nearly succeeded. The Supreme Court overturned decades worth of interpretation of the Constitution’s Commerce Clause to find that it didn’t allow the penalty. But John Roberts saved the individual mandate by reinterpreting its penalty as a tax.

But Roberts also sabotaged the system by not allowing the federal government to withdraw all Medicaid funding from states that refused to expand Medicaid. This created a two-tier system where some states expanded Medicaid and others didn’t. Gradually, even red states like Oklahoma and Missouri expanded their programs, but 10 states are still holding out.

Republicans finished killing off the individual mandate in the Trump tax cut of 2017, which didn’t eliminate the penalty, but set it to zero. This created a hole in the system: If you’re healthy right now, you can save money by going uninsured, remaining confident that you can get insurance after you develop some health problem.

The RSC’s 2019 report castigates ObamaCare for this hole in the system, which the Republicans created themselves.

Unfortunately, because the ACA created a perverse incentive for people to forgo insurance until they developed an illness, costs across the board rose dramatically, which required higher premiums on the existing plans in the individual market exchanges. Not surprisingly, the premium spikes further repelled healthy individuals.

How Republicans want to “fix” ObamaCare. If you don’t think ObamaCare is working, the obvious way to fix it continues to be a universal single-payer healthcare system, like Bernie Sanders’ Medicare for All. Countries with such systems continue to spend less on healthcare than Americans do, while getting better results in terms of life expectancy.

But Medicare for All is still socialism, which is still anathema. So what can be done?

The report is full of wonderful-sounding words like “choice” and “freedom”, but the essence of it comes down to this: The healthcare system can save enormous amounts of money if it exposes people to more risk.

I’ll give a personal example here: In 2023 I had a scary incident where I lost vision in my right eye for about five minutes. It was like looking at a gray screen. Afterwards, I returned to normal, as if nothing had happened. I’ve had no recurrences in the two years since.

All indications point to this incident being just one of those annoying brain things without long-term significance, like migraine headaches. But it could have been a stroke or a blood clot or a tumor. Medicare spent an huge amount of money checking all that stuff out. I didn’t keep track, but I’m sure it’s well into the tens of thousands.

And it all could have been saved if someone had said, “It’s probably nothing. Let’s ignore it and see if it happens again.”

Now, if some government or insurance bureaucrat says that, it’s horrible. They’re telling me to gamble with my life. But (from the Republican point of view) if I say it, that’s great. So that’s the heart of the Republican program: incentivize people to gamble with their lives.

They do this in a lot of different ways. For one, junk insurance is back.

[I]n order to provide Americans with health insurance options that fit their individualized needs and do not add unnecessary expenses, the RSC plan would undo the ACA’s regulations on essential health benefits, annual and lifetime limits, preventive care cost-sharing, dependent coverage, and actuarial value. … The cumulative effect of these changes would result in Americans being provided with more insurance choices that are personalized to their needs and available at affordable rates.

(“Actuarial value” is essentially a limit on the insurance company’s profit margin.) So if you have a strained budget, a cheaper plan that risks your future if you wind up with some expensive condition is “personalized” for you. It “fits your individualized needs”.

Several provisions are designed to promote individual plans that can be “personalized” in this way. The biggest is to change the tax laws that allow employers to deduct what they spend on employees’ health insurance. With ObamaCare’s employer mandate also gone, this will have the effect of ending a lot of employer-supplied health insurance, pushing all those people into the individual market.

The other big “personalization” tactic is to emphasize Health Savings Accounts. Lots of people have those now for medical incidentals like glasses. But under the Republican proposal, HSAs are cut loose.

Under current law, health savings accounts plans cannot be used in conjunction with plans that are not a “qualified high-deductible health plan.” This unnecessarily hamstrings the ability for millions of Americans to access this important savings tool. Accordingly, the RSC would eliminate this requirement to allow health savings accounts to be utilized even if a person does not have a health insurance plan.

So you can go without insurance and pay your own health expenses out of an HSA. This is the ultimate individualization: Imagine me with an HSA instead of Medicare. My vision blanks out for five minutes, and I’m left with a choice: Do I want to drain my HSA checking out things that probably are OK? Or do I want to just risk it?

The limits of freedom. The unexamined issue in the Republican plan is class. Yes, you have “choices”, but only if you can afford to pay for them. The poorer I am, the more likely I am to risk a junk policy to save money, and the more likely I am to forego testing or treatment if I think it probably works out for me. Those are “choices”, in the same way that poor people “choose” to save money on rent by living in their cars.

Of course, when you’re talking about 350 million people, “probably” leads to many, many cases where the improbable happens. So these personalized decisions will lead to large numbers of medical bankruptcies, and some non-trivial number of unnecessary deaths.

The other thing “freedom” doesn’t take into account is the burden of making good decisions, especially decisions about big issues that involve many details that only experts in the field really understand. As we saw in the real-estate crash of 2008, “freedom” in the mortgage market led to people signing documents they didn’t really understand and losing their homes. More recently, “freedom” from vaccine mandates is allowing diseases like measles and polio to come back.

And if we are all making these decisions as individuals, the success of insurance or healthcare-providing companies depends on their ability to influence those decisions. Think about all the ads you see this time of year boosting “Medicare Advantage” programs (which provide enormous advantages to the companies offering them). That kind of marketing could be round-the-clock for every kind of medical decision. Just as the system forced us to make more decisions, all the corporate powers of persuasion would be focused on manipulating us into choosing badly.

All that marketing would cost an enormous amount of money, which ultimately would have to be reflected in the prices we pay. Would it eat up all the “savings” that result from taking bigger risks with your life? Maybe.