Worldwide inflation has been a lingering symptom of the Covid pandemic. Trump and Biden share blame for the US inflation, and reelecting Trump won’t fix it.

Polls show that voters trust Trump more than Biden (and probably Harris) on economic issues, and the main reason for that is the inflation we’ve seen since Biden took office. The Republican platform and Trump’s convention speech both appealed to that issue, claiming that Trump will “end inflation … very quickly”.

A few things get lost in this promise, like:

- Inflation is already ending, just as the Great Recession had already ended when Trump took office in 2017. So all a reelected President Trump will have to do to “end inflation” is to announce that it’s over. That can happen “very quickly”.

- The low gas prices Trump’s supporters point to weren’t due to his energy policy. They came from the fact that the economy was shut down for Covid and nobody was driving.

- Post-Covid inflation has been a worldwide phenomenon. Any explanation that pins the blame on Biden alone is simplistic.

- Many of Trump’s policy proposals will increase prices, not lower them.

But rather than point fingers about inflation, let’s see if we can tell its story in a way that makes sense.

The roots of the recent inflation stretch back to the Covid pandemic, which reached the US in 2020, the final year of Trump’s term. That seems like a weird claim to make, because in 2020 itself, the threat was deflation. Gas prices, for example, dropped to an average of $1.84 in April, 2020, because the economy was largely shut down. If you had gas to sell, few people were buying. As the economy contracted and more and more people lost their jobs, the economic threat was a Depression-style cascade of bankruptcies: My business is closed, so I can’t pay my suppliers or landlord, so they go bankrupt and can’t pay the people who were counting on them. And so on.

But let’s tell the story from the beginning. Today, after a vaccine and treatments like Paxlovid have been developed, and after the virus itself has evolved into less lethal forms, many of us have repressed our memories of just how terrifying the early months of the Covid crisis were. At the time, the only treatment to speak of was to keep patients’ blood oxygen up in any way possible, and hope that if they didn’t die their immune systems would eventually win out.

In the early places where the infection got loose, such as Italy and New York City, it overwhelmed the health-care system. Sick people languished on cots in hallways, and refrigerator trucks supplemented the morgues. A lack of good data made it hard to determine just how lethal the virus was. Nobody knew how many asymptomatic cases hadn’t been noticed, and the number of Covid deaths might be either higher or lower than death certificates indicated. But the early estimates of lethality were around 3%; about 3% of infected people died. (That later got revised downward to 1.4%.)

So governments faced a lose/lose choice: If the virus were allowed to run wild, probably everyone would get it eventually, so about 3% of the population would die. In the US, that would mean over 10 million people. (The 1.4% rate implies around 5 million American deaths.) The alternative was to shut down non-essential activities where crowds of people might gather and spread the infection: sports events, political rallies, churches, concerts, and so on. Additionally, bars and restaurants, schools, movie theaters, factories, and offices were likely to spread the virus. When social interactions were unavoidable, governments could encourage masking and social distancing.

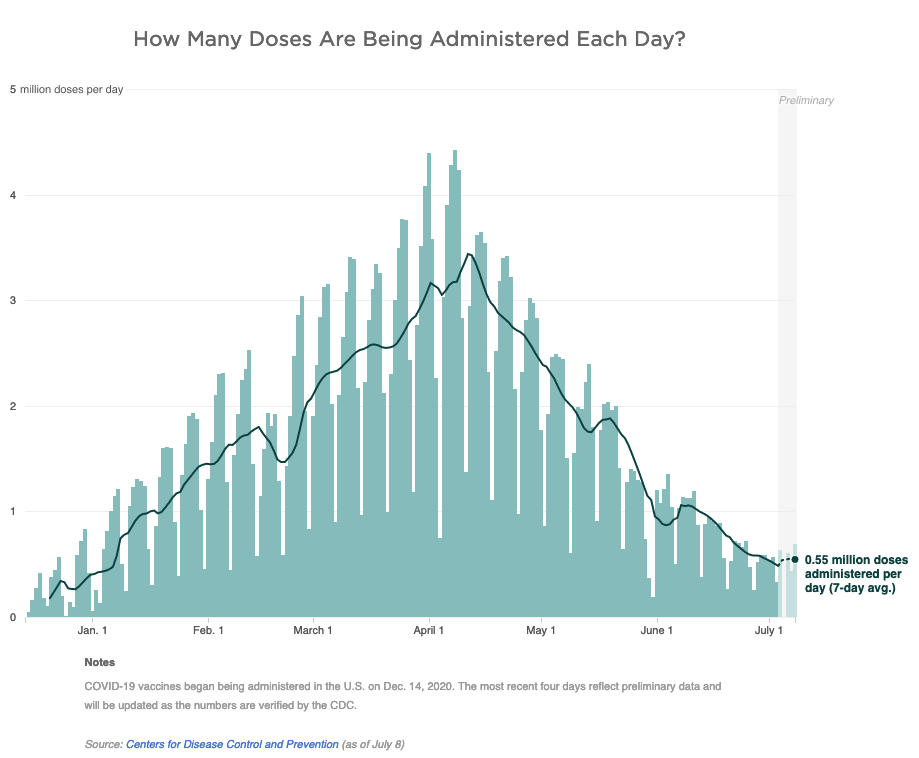

The point of all this wasn’t to defeat the virus, but to slow it down. The hope was that a slower-spreading virus wouldn’t overwhelm the healthcare system (“flatten the curve”, we were told), and that extra time might allow discovery of better treatments or a vaccine. That more-or-less worked out: In the US, “only” 1.2 million died, rather than 5-10 million. (If we had handled the virus as well as Canada, perhaps fewer than half a million Americans would have died.)

But there was a cost. The unemployment rate went over 14%, and that was an undercount. Millions of other Americans continued to receive a paycheck, but weren’t really working. (A government loan program allowed small-business loans to be forgiven if a business maintained its payroll.) What was going to happen to those unemployed through no fault of their own? What good did it do to keep them from getting sick if they were going to lose their homes and starve?

Again, a lose/lose choice: In order to avoid mass poverty, cascading bankruptcies, and economic destruction that might take years to recover from, governments propped up people’s incomes. In the US, I already mentioned the loan program. Unemployment benefits were repeatedly extended beyond their ordinary expiration dates. State and local governments got federal money that allowed them not to fire their employees. Landlords weren’t allowed to evict non-paying tenants. Occasionally, the government would just send everyone a check, whether they were covered by some income-protection program or not. Other countries took similar steps.

Because tax revenues were collapsing at the same time that governments were taking on these additional expenses, deficits skyrocketed. The largest US federal budget deficit ever came in FY2020 (October 2019 through September 2020), the last year of the Trump administration: $3.13 trillion. The next year (1/3 Trump, 2/3 Biden) was nearly as bad: $2.78 trillion.

What that money was doing was even more inflationary than the deficit itself: People were being paid not to produce anything. So: more money, but fewer goods and services to spend it on. This was inevitably going to increase prices.

But inflation didn’t hit right away, because people confined to their homes didn’t spend much. There was no point buying a new car, for example, when your current car was sitting unused in the garage. The cruise lines and theme parks were shut down, and no one wanted to risk spending hours sitting elbow-to-elbow in an airliner, so vacation spending collapsed. You had to keep buying food, but beyond that, the richer half of households worked from home, cashed their government checks, and let their money sit in the bank.

But when the economy opened up again, all that money was bound to come out and drive prices upward. In addition, not everything restarted at the same rate, so the economy developed bottlenecks that increased prices further. The Ukraine War disrupted the world’s grain and oil markets, adding additional inflationary pressure.

Post-Covid inflation was a worldwide phenomenon that peaked in 2022, when US inflation was 8%. Bad as that was, things were even worse in comparable economies like the UK (9.1%) and European Union (8.8%), while some smaller countries saw catastrophic levels, like Turkey at 72.3% and Argentina at 72.4%.

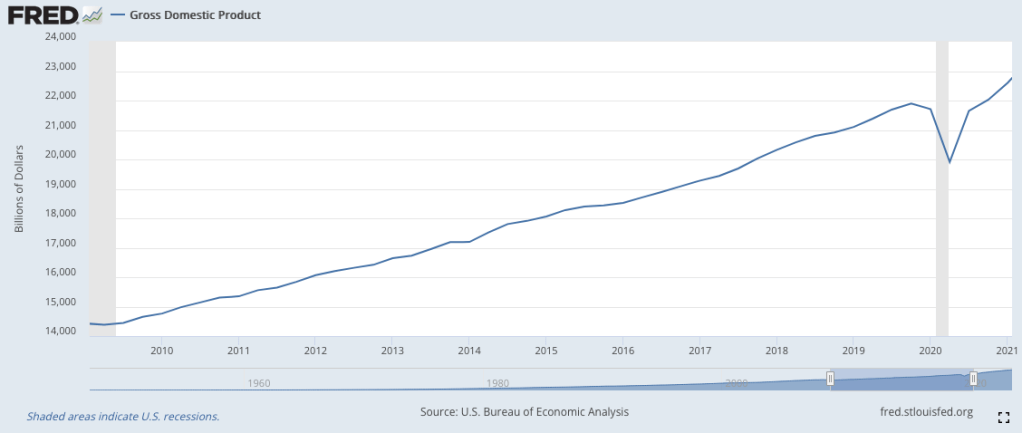

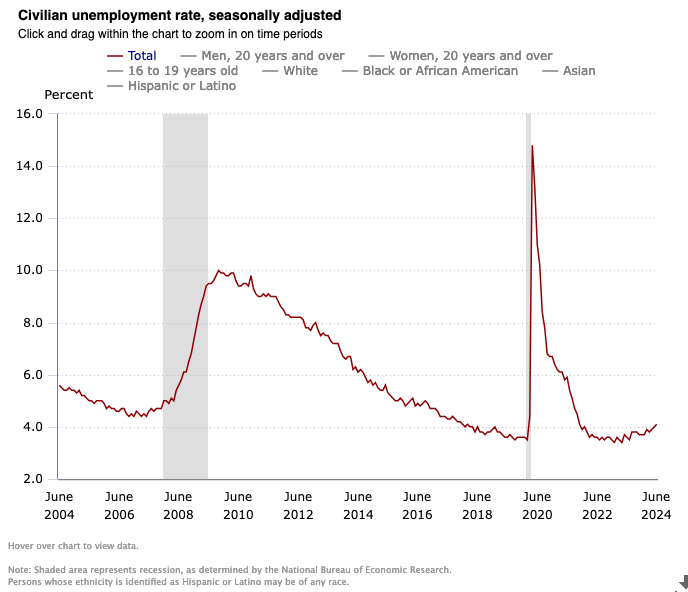

The final lose/lose choice was how fast to restart the economy. Unemployment was still over 6% when Joe Biden became president, and he had learned a hard lesson from the aftermath of the Great Recession. The stimulus spending President Obama had managed to secure during the two years when he had congressional majorities wasn’t sufficient, and after 2010 he battled Republican leaders in Congress for every penny. The result was an economic recovery so slow that many Americans barely noticed it. Not until 2016 did economic indicators return to the normal range. They continued upward from there, allowing Trump to take credit for “the greatest economy ever” when the trends Obama established continued into his term. (Look at the GDP and unemployment graphs below and see if you can pick out when the “Trump boom” started.)

Given Obama’s experience, Biden opted for a faster restart. To his credit, he invested the stimulus money wisely: building infrastructure and laying the groundwork for a post-fossil-fuel economy.

But the main thing he bought with that spending was job creation. By early 2022, the unemployment rate was back at pre-Covid (“greatest economy ever”) lows, and went slightly lower still. But Biden’s stimulus exacerbated the inflation that was already due to arrive.

The Federal Reserve responded to that inflation by increasing interest rates, which has brought its own hardships. The US economy has been surprisingly resilient under those interest rates, but it remains to be seen whether inflation can be beaten without starting a recession. (As I write, data from a slowing economy is sending the stock market plunging.)

So the impact of the Covid pandemic continues to be felt.

Conclusions. Nostalgia for the pre-Covid 2019 economy is understandable, but thinking of it as “the Trump economy” is a seductive illusion. Trump’s main economic achievement was that he didn’t screw up the recovery that began under Obama.

When Covid hit, the effect was going to be felt somewhere: as millions of deaths, as depression, or as inflation. Trump and Biden made similar policy choices, taking on massive deficits to lessen deaths and avoid depression. The bill for those choices was inflation, which in many ways was the lesser evil. Even in retrospect, I can’t wish the US government had taken a different path.

That bill came due under Biden, but the responsibility for it falls on Trump and Biden alike. That’s not because either of them performed badly, but because the pandemic’s toll had to be paid somehow. Governments got to choose the form of payment (and most made similar choices), but not paying wasn’t an option.

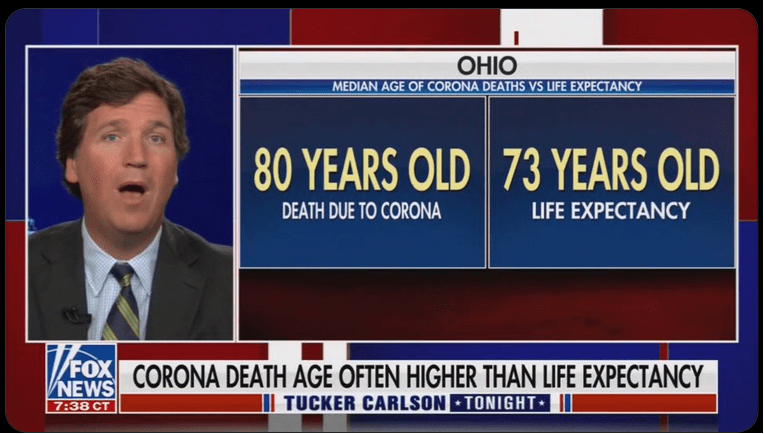

Trump’s primary talent is salesmanship, so he excels at taking credit for anything good that happens and avoiding blame for anything bad. His 2024 campaign has done an impressive job of selling 2019 as the typical “Trump economy”; if things got drastically worse in 2020, that wasn’t his fault. So if we just reelect him, he often implies, it will be as if Covid never happened. 2019 will magically return.

It won’t. Presidents do not wave magic wands, or move economies with their personal charisma. Presidents affect economies through their policies of taxing, spending, and regulation. So far, the policies Trump has put forward are vague and his numbers don’t add up. (The Republican platform promises to cut taxes, increase defense spending, rebuild our cities, maintain Social Security and Medicare at current levels, and yet reduce deficits by cutting “wasteful spending” that it never identifies. We’ve heard such promises before, and they never work out.) Some of his proposals, like a 10% across-the-board tariff on imports or deporting millions of low-wage workers, would increase inflation, not decrease it.

Whoever we elect in November, I can promise you one thing: 2025 will be its own year. It won’t be 2019 again.