Connecting the dots is meaningless if you’ve never established that the dots really happened.

I remember, almost to the minute, when I became a Democrat. As a teen-ager, I had libertarian leanings that I don’t like to talk about now. In my 20s and 30s, I was a left-leaning independent, but it wasn’t hard for a moderate Republican to charm me. I spent one afternoon of 1980 on a Chicago street corner, handing out pamphlets for John Anderson. In the early 90s, I was comfortable with William Weld as my governor.

And then in 1998-99 the Clinton impeachment happened.

I watched just about every minute of the televised trial in the Senate. I had voted for Clinton twice, and had been rooting for him all through the Lewinsky scandal. But still I watched the case against him unfold, because … what if the Republican impeachment managers had something? They seemed so sure that they did.

There were two counts. The first was perjury, and what it boiled down to was a he-said/she-said conflict over precisely which sex acts Bill and Monica had performed. Was Bill telling the truth? Maybe, maybe not. But in any case it seemed like a thin reed to hang an impeachment on.

The second count was obstruction of justice, and it hinged on why Monica Lewinsky had lied to the grand jury investigating Clinton’s harassment of Paula Jones. Monica had denied that she was having an affair with Bill, which everyone now agreed was perjury. But why?

There were a number of plausible explanations. Maybe she was embarrassed to have her sex life become a matter of public record. Maybe she still had some affection for Bill and wanted to protect him from a political scandal.

But there was a more nefarious explanation: Maybe Bill had asked her to lie, and had offered to find her a good job in exchange. Quid pro quo. Conspiracy to obstruct justice.

And this much was clearly true: One of Clinton’s top advisors, Vernon Jordan, was a director of the Revlon Corporation. Jordan got Lewinsky an interview at Revlon, which then hired her.

But the theory that this was a quid-pro-quo had a problem: Everyone up and down the line denied it, even the people who had no motive to lie. Clinton denied it, of course, and so did Jordan. Jordan claimed he often helped out White House interns, and Clinton would not be the first powerful man to do a favor for a young woman after an affair. So you didn’t have to assume obstruction to make the story work.

Lewinsky denied it, even though she had immunity, and so the only way she could get in trouble now was if she lied again. And the folks at Revlon denied that Jordan had put any undue pressure on them; he just sent Lewinsky over, and she got the job on merit.

What the Republican prosecutors did in their presentation was establish a timeline: They very meticulously proved that all the people who would have needed to conspire did indeed have communication with each other during the time period when the conspiracy would have needed to take place.

In other words, they connected the dots. They firmly established that the obstruction-of-justice scenario could have happened. They presented not a shred of evidence that it actually did happen. But it could have.

That was enough for 50 Republican senators to vote to remove the President of the United States.

I’ve been a Democrat ever since.

Conspiracy theorizing. Here’s what I didn’t realize at the time: The Lewinsky obstruction presentation was a preview of the conspiracy-theory culture of the 21st century.

Just before Biden’s inauguration, the NYT published a profile of QAnon “meme queen” and “digital soldier” Valerie Gilbert. It was supposedly a moment of crisis for the movement, because none of their predictions of a Trump victory or a “storm” of arrests of high-ranking Democrats and leading celebrities had come to pass. Trump really had lost the presidency, and Biden was about to take over. Q himself had gone silent.

But Ms. Gilbert isn’t worried. For her, QAnon was always less about Q and more about the crowdsourced search for truth. She loves assembling her own reality in real time, patching together shards of information and connecting them to the core narrative. (She once spent several minutes explaining how a domino-shaped ornament on the White House Christmas tree proved that Mr. Trump was sending coded messages about QAnon, because the domino had 17 dots, and Q is the 17th letter of the alphabet.)

When she solves a new piece of the puzzle, she posts it to Facebook, where her QAnon friends post heart emojis and congratulate her.

This collaborative element, which some have likened to a massively multiplayer online video game, is a big part of what drew Ms. Gilbert to QAnon and keeps her there now.

“I am really good at putting symbols together,” she said.

But think about what she’s not doing, which is any of the traditional work of investigation. She’s not finding and interviewing witnesses to key events. She’s not checking their stories against the kind of facts that can be nailed down. She’s not tailing suspects to see where they go and who they meet.

Instead, she’s connecting the dots. She’s coming up with ever more satisfying (to her QAnon online community) stories that pull together the high points of events that they assume happened. Did they happen? Hardly anyone seems to be working on that. The dots are the dots. What’s important is weaving them into a story.

Real investigating. Real investigations are laborious and involve large chunks of time devoted to tedious activities. TV dramas tend to skip that part. You learn, say, that the police have traced an earring found at the crime scene to the shop that sold it, and you don’t see the dozens or hundreds of conversations with shops that didn’t sell it. You don’t see all the interviews with neighbors who slept through the break-in and didn’t hear the gunshot.

Investigators endure that tedium because real investigations work from the bottom up. They establish tiny little factoids, in the hope that eventually those atoms of truth will start to fit together like Lego blocks. You may have your suspicions about what the eventual answer will be, but you hold them lightly as you wait to see whether the facts will take you there.

Connecting the dots turns that process upside down. The “dots” are a collection of plot points that your audience either already believes or wants to believe. A real investigator would first drill down on those dots to make sure they’re actually true. (Like, is that really a “suitcase of illegal ballots” in the Georgia video? Turns out it isn’t.)

But a dot-connector works the other way around: Assuming the dots are real, what story can you tell to weave them together? In the end, it is the overall appeal of the story that validates the dots. That’s why dots keep coming back no matter how many times they’re debunked: They work so well in the larger narrative.

That’s also why it’s so hard to argue with a dot-connector: They have a good story to tell, and all you have are the messy details. Here’s a bit of Trump’s recent Meet the Press interview:

FMR. PRES. DONALD TRUMP:

We have thousands of essentially motion pictures of people stuffing the ballot boxes. Tens of thousands.

KRISTEN WELKER:

But, Mr. President, they’re not stuffing the ballot boxes. And you’ve been told that by your top law enforcement officials. But let’s stay on track, because we have so much ground to cover. We have policy ground to cover, Mr. President.

FMR. PRES. DONALD TRUMP:

You have people that went and voted in one place, another place, another place, as many as, I understand, 28 different places in one day with seven, eight, nine ballots apiece. They can’t do it anymore, because it would look too phony. These were professional people. They were stuffing the ballot boxes. It’s there.

KRISTEN WELKER:

Mr. President —

FMR. PRES. DONALD TRUMP:

I mean, it’s there to see. A lot of people don’t like looking at it.

KRISTEN WELKER:

— you took your case to court in 60 different cases all across the country. You lost that. But let’s stay on track because we have so many —

FMR. PRES. DONALD TRUMP:

We lost because the judges didn’t want to hear them.

KRISTEN WELKER:

Mr. President, we have so many topics to cover.

Doing any actual debunking of Trump’s claims would involve going into those tedious details, and Welker doesn’t have time for that. Viewers would tune out. So she has to let the lies stand and move on to other topics.

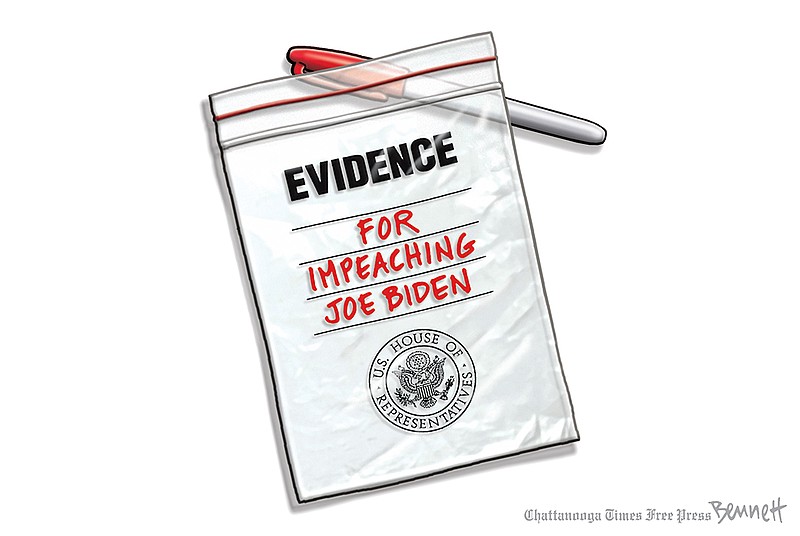

Connecting the Biden impeachment dots. The Biden impeachment investigators in the House have little evidence, but they have a good story to tell: Biden used his political power to protect his son Hunter, and Hunter in turn used his businesses to collect bribes for his father Joe. Put it all together, and throw in Joe’s brother James, and you have “the Biden crime family”.

The problem is that no piece of that story holds up to scrutiny, except that Hunter leveraged his name to make business connections that were almost certainly unethical, though probably not illegal (and nowhere near as corrupt or lucrative as Jared Kushner’s $2 billion from the Saudi sovereign investment fund). Some of the dots were debunked years ago, while others just lack any supporting evidence.

But if you want to believe that story — and a lot of people do — then the story itself validates the dots, even the ones that have repeatedly been shown to be false. That’s what reality-oriented people will be up against in the coming months.