As mass production has to be accompanied by mass consumption, mass consumption, in turn, implies a distribution of wealth … to provide men with buying power equal to the amount of goods and services offered by the nation’s economic machinery. Instead of achieving that kind of distribution, a giant suction pump had by 1929-1930 drawn into a few hands an increasing portion of the currently produced wealth. … In consequence, as in a poker game where the chips were concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, the other fellows could stay in the game only by borrowing. When their credit ran out, the game stopped. — Marriner Eccles, chairman of the Federal Reserve 1934-1948

In this week’s Sift:

- The Deficit Shell Game. For years we’ve been borrowing money to give tax cuts to the rich. Now the chairs of the Deficit Reduction Panel are delivering the bill to the middle class.

- The Sift Bookshelf: Aftershock by Robert Reich. A skewed distribution of wealth isn’t just unfair, it’s bad for the economy.

- Political Notes. I don’t have a Big Theory about the meaning of the midterm elections. But I do know a few lesser things.

- Short Notes. Maddow interviews Stewart. Don’t get leukemia in Texas. Scientists discover new reptiles in restaurants. The Chinese are serious about clean coal. Why Glenn Beck is not (quite) an anti-Semite. What comic books can tell us about religion. And more.

Suppose a major political party went to voters with this message: “We’re going shrink every program that the middle class and the poor depend on: Social Security, Medicare, unemployment compensation, Medicaid, and so on. And with the money saved from those cuts, we’ll give big tax cuts to the rich.”

It would never fly. Rich people would support it, of course, and the party might get as much as 30-40% of the vote if they successfully demonized their opponents. But the bald message that the rich should have more and everyone else less has never been popular.

But here’s a funny thing: If you split the proposal by putting the word deficit in the middle, and if you’re careful not to discuss the two halves of your program in the same conversation, people go for it.

In Step 1, you promote tax cuts that throw a few pennies to everyone, but are focused on the rich. At this point in the process you argue that taxes are bad, because the people who earn money should get to keep it. You paint the Government as a huge black hole that eats up money without anything ever coming out. If pressed, you pledge to cut “spending” — that amorphous mass of “waste” that could go away without hurting anybody.

Then, after you get your tax cuts passed, you come back a few months later with Step 2: “Oh my God! There’s a deficit!” Because of course no one could have predicted that cutting taxes would lead to less revenue and more borrowing.

Suddenly the deficit — which you carefully kept out of the conversation when you were talking about tax cuts — is the Worst Problem Ever. And now that we’re distributing pain instead of bushels of money, everybody is in this together. Suddenly there is no “waste” to cut effortlessly. We all have to “tighten our belts”. The government has “made promises it can’t keep” (at least not at this tax level), so programs will have to be cut across the board — especially the entitlements that go mostly to the middle class.

The latest version of this shell game — the proposal from the “bipartisan” chairs of the Deficit Reduction Panel — is the most blatant I’ve ever seen. If you look at their slide show, you’ll find proposals to cut everything under the Sun — including rich people’s taxes. The slides say that “It is cruelly wrong to make promises we can’t keep” and “A sensible, real plan requires shared sacrifice – and Washington should lead the way and tighten its belt.”

Washington here is a euphemism for people who were counting on government programs — old people, sick people, veterans, the unemployed, and so on. They — and not the rich — need to tighten their belts. While the middle class has to figure out how to retire later, co-pay more of their Medicare expenses, and do without a bunch of other benefits, the tax rate paid by the richest Americans falls from 35% (currently) or 39.6% (if the Bush tax cuts aren’t extended) to 23%. And the corporate tax rate falls from 35% to 26%. Paul Krugman sums up:

this proposal clearly represents a major transfer of income upward, from the middle class to a small minority of wealthy Americans. And what does any of this have to do with deficit reduction?

Amusingly, on the same day I started writing this article, La Feminista made the same point, even using the same term “shell game” to describe it.

A more intellectual critique of the government-has-to-tighten-its-belt approach is Daniel Greenwood’s Prosperity Comes From Justice, Not Austerity in Dissent.

The books I’ve reviewed lately all share a theme: the distribution of wealth. Winner-Take-All Politics described just how skewed the distribution has gotten, and how government policies have helped the ultra-rich pull away from everyone else. Were You Born on the Wrong Continent?demonstrated that it doesn’t have to be that way by using the example of Europe: A 21st-century economy can provide a decent life for everyone. Health care can be a right. Workers can have a say in how their workplaces are organized. Consumption can focus more on public goods like parks and less on private goods like estates. It works.

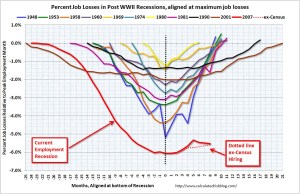

Now Robert Reich has come out with Aftershock: The Next Economy and America’s Future. Reich is coming at the same message from the opposite direction: The winner-take-all economy doesn’t work, even on its own terms. He makes this point by comparing three eras in American history:

- 1975-to-now, when wealth has been concentrating;

- a similar period in the 1920s, leading up to the Great Depression;

- what he calls the Great Prosperity, the 1948-1975 period when wealth was spreading out

The singular virtue of the Great Prosperity was that supply and demand matched, and each pushed the other higher. In a healthy industrial economy, mass production and mass consumption go together. The people who make things earn enough money to buy the things they make. Carpenters can afford houses. Auto workers can afford new cars.

But when the distribution of income gets too skewed towards the rich, you get the bubble economy of the 20s and the last two decades. The financial economy separates from the real economy and goes through a series of speculative booms and busts.

The best account of the boom-bust cycles of the 20s is Fred Lewis Allen’s classic Only Yesterday, which looks back on the 20s from the sadder-but-wiser perspective of the Depression.

After the Florida hurricane, real-estate speculation lost most of its interest for the ordinary man and woman. Few of them were much concerned, except as householders or as spectators, with the building of suburban developments or of forty-story experiments in modernist architecture. Yet the national speculative fever which had turned their eyes and their cash to the Florida Gold Coast in 1925 was not chilled; it was merely checked. Florida house-lots were a bad bet? Very well, then, said a public still enthralled by the radiant possibilities of Coolidge Prosperity: what else was there to bet on?

That’s not just a coincidence; Bubbles are a predictable feature of an economy skewed towards the rich. Reich does an excellent job of explaining why.

Stop me if you’ve heard this. I’ve used this example before to explain the illusion of saving money, and how that makes the financial economy different from the real economy. If it’s obvious to you, skip to the next section.

Before money came into the picture, “saving” meant putting aside real goods. You spent the harvest season stockpiling and canning and preserving so that you could eat through the winter.

Compare that to what might happen today: All summer a college student makes pizzas and saves money. All winter he spends his saved-up money buying pizzas. On the surface this pattern resembles the canning-and-preserving practice, but all those summer pizzas got eaten or thrown away during the summer. No pizzas were put aside, only money.

That’s typical. When you save money, your “savings” is an illusion of the financial economy; the real economy isn’t saving anything. What makes this trick work is the banking system: It circulates your saved money by loaning it to people who will spend it, either to consume something they hope to pay for later, or to invest in something they hope will be productive someday.

Excess saving leads to depression. But everything falls apart if everyone tries to save money at the same time. Because then the only way to work things out is to stop production. (No matter how many people want to make pizzas, if no one is willing to buy them, even on credit, the pizza shop closes.) This can turn into a vicious cycle: Falling production means falling profits and people getting laid off. That scares the people who still have jobs, who save more; and it intimidates the people who might invest in new production, because they don’t see who they’re going to sell their new products to.

Concentrated wealth and bubbles. Now think about what happens when too much of an economy’s income goes to the ultra-rich. The kind of money the ultra-rich make isn’t consumable. (In 2009, the top seven hedge fund managers each made over $1 billion. You just can’t spend that kind of money.) So it gets saved.

If production isn’t going to drop, that saving has to get borrowed and spent by someone else. But who? There’s a limit to how much debt the middle class can carry, so ultimately the savings of the ultra-rich has to be borrowed by other ultra-rich people. We’ve already seen that they can’t consume their income, so they will have to invest it. But in what? If they invest it in increasing production — new factories, new shops, new services — that just kicks the can down the road. Who do they imagine is going to buy their increased production when it comes on line?

Consequently, the money has to go into bubbles: Speculators borrow to bid up the prices of non-productive assets. That’s not some strange accident; it’s what has to happen when the distribution of income gets too far out of whack.

So in the 20s you had a series of land bubbles — Florida, the suburbs — followed by the stock market bubble that popped in 1929. (Stock market bubbles look like productive investments, but they’re really not. Only money invested in new stock goes into the real economy in the form of new factories, shops, and services. Otherwise you’re just bidding up the price of existing assets and not increasing production.) Or, more recently, you get bubbles in internet stocks or houses or gold or oil.

The basic bargain. World War II was the biggest unintentional redistribution of wealth in American history. That’s what ended the Depression. By taxing and borrowing, the government collected massive amounts of money from the rich and paid it out to soldiers and factory workers and farmers and miners.

After the war, veterans benefits together with the legal and social mechanisms established during the New Deal kept the money from flowing back to the rich: not just high taxes on high incomes (tax rates topped out over 90% and stayed that way until the 60s), but educational benefits, Social Security, unemployment insurance, and laws that made it easy to form unions.

The result was what Reich calls the Basic Bargain: If you participate in mass production, you should make enough money to participate in mass consumption. That bargain was the basis for the most widely-shared prosperity in American history.

Since Ronald Reagan we’ve been undoing that bargain, with the result that wages have stagnated even while productivity grows. The pie is bigger, but workers get an ever-smaller slice. At first, middle class households kept spending by sending more women into the workforce. Then they kept spending by borrowing against the bubble-inflated value of their homes. In 2008 their credit ran out and the game stopped: Middle class demand can’t drive the growth of the economy any more.

Restoring the basic bargain. Reich closes with a number of proposals, some of which (like a carbon tax) are more generically liberal than related to the case he has been making. But his largest proposals are a reverse income tax (sharply higher rates for the rich combined with wage subsidies for the working poor), extending Medicare to everybody, and increasing spending on public goods like parks, libraries, and public transportation.

Unions are a key part of the case Reich is making, but he says little about changing the labor laws. I think labor-law reform is an important part of solving the income-concentration problem.

Think about what a “good job” is. In the collective discussion about the working class, we’ve tended to use the terms good job and manufacturing job interchangeably, as if there were something magical about factories that can’t be duplicated in service industries.

But the magic of the factory jobs of the 50s, 60s, and 70s was this: They were in unionized industries where wage increases could be absorbed by the owner or passed on to the customer. Many service jobs could fit this description, if its workers were organized.

For example, consider baristas at Starbucks. Payscale.com estimates that they average $8.63 an hour. (A Starbucks store manager gets only $13.) But the price of a cinnamon dolce latte has nothing to do with the cost of making it, and there’s no reason that an organized workforce couldn’t force a better deal out of the company. (Some workers are trying.) A cashier at Whole Foods — another place where prices have little to do with cost — starts around $8 an hour and averages about $10.

No law of economics says that retail and other service jobs can’t be good jobs. Workers just need to organize across entire industries, so that non-union stores can’t gain an advantage over union stores. (That’s hard, but government help would make it easier, if government got back to representing people instead of money.) Prices at Wal-Mart would go up, but we might have a stable middle class again, and a growing economy.

For the last two weeks the airwaves have been full of speculation about what the mid-term elections meant and what will happen now that the Republicans control the House. I don’t have a Big Theory that explains it all and tells us what to do next, but I do know a few things:

The voters rejected a straw man. I’m reminded of 2002 and 2004, when voters were still blaming Saddam for 9-11. Voters this year believed all kinds of false things: that Obama had raised taxes when he had in fact cut them; that health care reform raises the deficit when it actually lowers it; that government is growing like a tumor, when both federal spending and the number of government employees dropped in fiscal 2010. And let’s not even get into the numbers of voters who believe that Obama is Marxist Kenyan Muslim imposter.

It’s hard to know what to do with that. People who argue that Obama should “move to the center” seem to imagine that more conservative policies won’t or can’t be painted as the beginning of the Communist revolution. But you would have thought that about using Mitt Romney’s health-care ideas, too. Whatever you do, people can lie about it if they want to.

It’s not 1995. The Gingrich Revolt of 1994 foundered when the Republican Congress shut down the government in 1995. People don’t like the idea that their Social Security checks will be late, and they mostly blamed the Republicans.

But Fox News didn’t launch until 1996. Today a powerful conservative media machine will justify whatever the Republicans do. If they shut down the government (in February, when Congress will need to raise the ceiling on the national debt), no one knows who the public will blame.

If there is a government shut-down, watch the stock market. The Republicans will not bat an eye if grandmothers are begging on the streets, but if the stock market plunges they’ll have to do something.

Or maybe it is 1995. I expect a series of pointless investigations as the Republicans search for some excuse to impeach Obama. If they follow the Clinton-era pattern, they’ll raise a lot of Fantasy-gate issues hoping to stop Obama’s re-election, then move towards impeachment if that doesn’t work.

The Republicans ran on nothing, and have no agenda now. The closest thing they had to a policy proposal was “cut spending”. They never specified what spending, and there aren’t several thousand bridges-to-nowhere they can cancel. Any major spending cut means changing policies that the American people support, like raising the retirement age.

You can’t compromise with “there’s no problem”. Democrats want to do something about people without health insurance and Republicans don’t. Democrats want to do something about global warming and Republicans don’t. Where can they compromise?

Thursday night my two favorite TV hosts were on the same screen: Rachel Maddow interviewed Jon Stewart.

Stephen Colbert interviews the head of the last American manufacturer of marbles, and finds out that Obamacare is actually good for small business.

If you’re a biologist hoping to catalog a previously unknown species of lizard, where should you look? Try a menu.

American Prospect’s Gabriel Arana explains why the bullying gay teens face is different:

It’s not just the schoolyard jerk who picks on you. It’s the pastor who rails against the “gay agenda” on Sunday, the parent who stands up at a city council meeting and says he moved to your city because it’s “the kind of place that would never accept the GLBT community with open arms,” and politicians like New York’s would-be governor Carl Paladino, who on the campaign trail said things like “there is nothing to be proud of in being a dysfunctional homosexual.” Even once you get past high school, you still can’t get married or serve in the military, and in most states, your employer can fire you just for being gay. This is the kind of “bullying” gay kids face, and it’s the kind no one’s standing up to.

I had two preconceptions when I started reading this article: James Fallows is a serious guy, and clean coal is not a serious idea. Something had to give.

The gist: The Chinese have done the math, and no credible quantity of alternative energy will allow their billion-plus people to join the 21st century. Oil is eventually going to run out, so either they’re going to figure out how to burn coal cleanly, or they’re going to wreck the planet. That vision gives their research an urgency that American research lacks.

Glenn Beck isn’t an anti-Semite. He just uses anti-Semitic stereotypes to demonize Jews he doesn’t like. See the difference?

The Daily Show explains why Missouri’s new ban on “puppy mills” (huge warehouses raising dogs for sale) is a step on the road to Communism. (Includes a guest appearance by the Dog Whisperer, Cesar Millan.)

The next time someone tells you that our health-care system is the best in the world, have them read “Too bad we can’t afford to treat your leukemia” by an anonymous Texas doctor.

If a generation of kids expected something different from superheroes twenty years ago, maybe they’ll expect something different from religion now that they’re adults. At least that’s what I claim in the current issue of UU World.

The Weekly Sift appears every Monday afternoon. If you would like to receive it by email, write to WeeklySift at gmail.com. Or keep up with the Sift on Facebook.